Tags

Story and Photograph by Sandshoe

Driving to Cairns on the last leg of the Pacific Highway in those days, coming out of Gordonvale you turned onto Cairns Road left off the main street just before the level crossing. Norman Street is the main street and we lived round the corner on Cairns Road at Number Seven.

The Sunlander went through and sirened a blast of warning at the crossing. The passengers waved from behind sealed windows. The local rail motor stopped at a siding at the crossing. Railmotor passengers leaned out open sash windows. Some shyacked with fellow travellers by leaning out of windows the length of the carriages.

Passengers at their destination at the stop climbed down a ladder of steps into dirt.

A bungalow over the crossing teetered on tall black posts behind a passenger shelter at the rail stop. Beating tropical sun faded its paintwork and iron roof. The brick nurses quarters directly over the other side of the tracks from us looked to me like joined pieces out of a farm building set I used to think someone would come back for one day and take home to the kid who owned it. A wide roadside verge of kikuyu grass on both sides of the road between us was made tidy by a tractor driver who dragged a slasher over it. Molasses grass that grew wild along the railway line was reduced by controlled burning.

A ganger pushing a trolley car was derailed. He told my mother his life story when she ran to help him. She recounted at the dinner table he was addicted to tea leaves. His greatest despair was his addiction.

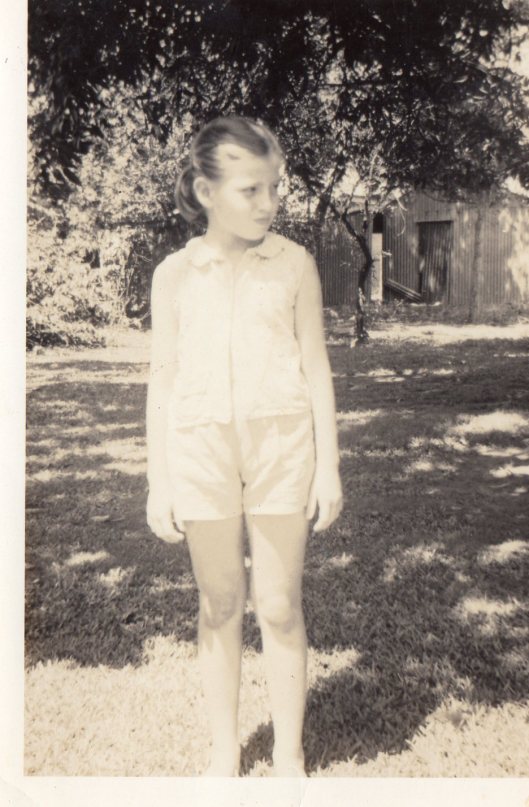

Over the crossing a thin black child who was a school friend stands motionless beside a black woman. Tin lean-tos swathe the out-of-town edge past the cemetery. My feet push alternately on my bicycle pedals forward and down. The gathered fabric of the skirt of my dress slides backwards and forward over one knee and the other. A reversal of my weight on the pedals slows the bicycle. I circle to stop. My feet firm on the ground and my legs straddling the bicycle frame, I bend over to retrieve a ribbon fallen off a hair plait. Placing my feet on the left hand side bicycle pedal I stand and lean forward. The pedals start to turn and the wheels spin.

Sugar cane flowers on tall stems flustered a feral clump of sugar cane beside the road. A light breeze was sweet. The tyres of the bicycle made a strrip-strrip sound where the road’s surface changed from bitumen to concrete paving. Past the Council depot on the right hand side of the road, cane train tracks delved an altered rhythm into the sound of the bicycle tyres strrip-strriping.

Sugar cane became an avenue broken by occasional cleared spaces enough for a farm home. In the season cane cutters dossed in farm barracks made of sheets of iron for walls and roofs. I rode the length of the concrete and turned around for home. The time was stolen. Nobody knew where I was. I liked that.

Home one day I wondered by instinct if the horse was gone. The man her mother chatted with over the fence down the back yard time to time was training a horse. Her mother said to win money. Other people were involved. A stable of sheets of corrugated iron for walls and hessian bags were higgle piggle at the back next door. I called out to my mother.

The red and blue skipping rope turns on the ground under my feet. It connects with rotting mango and flings a string of semi-dried pulp and skin into the air.

My mother was crying out to me in a querulous voice from inside the house.

The skipping was ritual. I could turn the rope in arcs over my head and cross hands, alternately change the arc to skip backwards.

My mother was calling again and I heard a deep concern for me. I ran to the house. My mother was coming down the steps.

“You need to know.”

I just knew. The horse was dying or dead. I followed my mother whose heel turn at the back door was brisk. The floorboards under the yellow and black linoleum made a creaking sound as they shifted. At the end of the kitchen the waving branches of the maroon and yellow and red tree hanging with a luxury of seed tassels brushed on the exterior wall beside the window above the kitchen sink. There was often a leather head with a querulous eye there in the frame of the window. Not that I noticed that day. My mother exited the door into the criss-cross patterns of hot shadows on the side verandah. She said as she walked in front of me there had been an accident.

The earth drainage culvert on the other side of the road from the vacant block next door was spanned by a wooden foot bridge. The horse had fallen under the foot bridge.

We walked together down the concrete front path. My mother had to go back to help the man . I had to wait. I walked back the length of the path to sit on the front steps of the bungalow.

Across the vacant block viewed to the left from the front steps, beyond the lemon tree and pawpaw tree, poinciana, casuarina and across another wide grassy verge outside its fence and across the road that came out on Cairns Road, a railing of the footbridge at the corner and the brown horse were broken together. The horse lying askew on its side was half-in and half out of the culvert.

Sitting on the front steps, I watched the tableau of people gathering and my mother was central. I felt a burst of mistrust for the man, not because my mother had an arm around him comforting him but because I believed in my sad heart of hearts it was his fault the horse had fallen under the bridge. I considered the elegant horse was walked across the wooden footbridge. As the years went by I wondered if I imagined the cause.

I might have imagined it with all its implications and he so different from the bustling full bosomed woman who regularly carried up to the corner of their shared back fence a coronation tray covered with freshly baked biscuits with a towel thrown over them.

“Mrs Wilson?” she remembered the woman calling to her mother and the branches of the mango tree creaking, “Mrs Wilson, some treats for your family and you with no mother anymore, you poor darling”.

Her mother was fine-boned and thin. Her neighbour exuded a physical largesse and high beam of feeling for the family she bestowed this love on. “Mrs Wilson”, she exclaimed one day, “You don’t have to worry about your family. Your children have such lovely manners. It’s like living next door to royalty.”

Immediately behind a high hedge of tangled yellow oleander at the back of the backyard was the back yard of a woman who was as well a woman living alone. I walked past her front door on her way to school in the morning. The woman was seated in the doorway in a cane chair. The husband was a man who had drank too much. He chased his wife with an axe. The poor woman had hidden in my grandmother’s house.

Was a man I wondered I had once seen in the garden the husband returned like a ghost returns.

The fence in the back corner where the stable took the place of shared niceties and treats passed over it was only strands of barbed wire. The backyard of their neighbour at the opposite corner was private behind an iron garage. For a while there was a Mr and boarders who were young men who worked in the bank.

One of the boarders was my teenage brother’s close friend in the final years of his high school. He scaled the ladder of the water tower in the park and stood on his hands on its rim. With my brother and a couple of their mates he made a canoe out of tin and sheets of iron to float down the Russell River. Our father conceded to drive the boys to the river with the canoe in the back of his work utility only to abruptly order the crew off the water in view of the height of a raging flood. Our father arrived home in an agitated state, “A man of his age,” he fumed, “he should know better. That river’s full of crocodiles.”

It was the friend’s idea they instead made spear-guns with barrels made of rough hewn wood. A series of looped wires ran through metal guides spaced the length of each barrel. Their father knew nothing of it until the boys carrying one of their friends in a manfully shared cradle of arms trekked the distance from the valley of the Little Mulgrave to a point on the open road where a farmer returned them to town and the ambulance. One of the guns discharged as the hunters walked along the bank of the river. Its metal spear lodged in the thigh of the next in line.

Our father’s rolling Scottish accent supported a sound grasp of the English language at the best of times. At his worst he was capable of a voluble tirade of swear words however infrequent and I never heard them. Johnny was a grovelling repentant. Johnny the bank johnny at the kitchen sink after Sunday lunch spun the dried butter plates into pirouettes for my mother to catch.

Our dare devil family friend became a minister of religion. The group were all church goers. They attended the Presbyterian church that was immediately around the corner on Norman street.

I was years younger than my siblings. I lived through rope petticoats and love affairs with scrap book idols Sandra Dee and Johnny Devlin as an observer. I sang ‘Jus wanna be a teddy bear’ with appropriate breathiness and intonations of depth when I was only 5 to my brothers and their friends playing drums and saxophone, my sister on the piano singing alternating with my mother on piano and our father on piano. Our father taught me to sing rock and roll. He was the leader of the Presbyterian choir nevertheless. We were younger than Springtime together. Cherry Ripe Cherry Ripe Ripe I cry. Full and Fair Ones. Count Your Blessing One by One. Carousel. The King and I.

My mother was a self-taught dance band pianist who thumped the piano by playing it by ear until the walls reverberated Ramona Ramona I hear the mission bells. My sister’s skirt flew up and her legs were bare when our mother taught the teenagers to foxtrot. The teenagers taught my mother to jive.

They were the days of the engines of motor bikes that burst into flame. Arguments between the boys and my father became common place. My brother whose birthday I crash landed on had an accident off the back of the scooter he and his best school friend were riding on homeward to his girlfriend’s place after a hockey match.

The father of my brother’s girlfriend happened to glance that early Saturday evening out of the window at the front of his home. He saw my brother catapult into the air higher than the electric wires and telephone cables, somersault and land back to earth again. Dux of the school and boy voted most likely to succeed he and his friend lay in adjoining cubicles in the Cairns hospital and my brother thought a reference he heard in a concussed daze that someone had died was to his school friend. They both lived. They both became economists.

My sister was a student of economics who became a teacher.

My oldest brother went off to join the railways.

I sat for years with my parents alone at home when my siblings were gone listening to their letters home read aloud; my economist brother’s written with passionate intensity to share mergers, acquisitions, companies I could name unerringly. I thought in a moment of logic and introspection I was privvy to confidential information about a redistribution of resources to the ever more wealthy.

One day one Christmas holidays when my siblings travelled home from their jobs in their respective cities our father enquired of them if they would share a Christmas whiskey. Our mother had a shandy. I was not allowed.

Our age of innocence is over.

I felt as though I was there ! Beautiful Shoe. So lovely to read you again.

LikeLike

I so appreciate it that you are here Vivienne. It is a great joy for me I was able to get back here to the pub for Christmas.

Thank you for the kind reference to my story. I am very happy for that.

LikeLike

Our dearest ‘Shoe. It’s masterfully written. OK I should have spotted the one typo and some mixed persons. I’ll fix the former, but the piece is so beautifully textured the persons stay.

Thank you for a really good read. Merry Christmas and a top notch year to come must be yours !

Fond regards,

Emm

LikeLike

Thank you Emm for your kind appreciation of my story. Thank you for posting it.

When I first started posting at the pub I suffered if there was a typo I had overlooked. It’s good to shed some of that concern. I appreciate we know what is meant.

Writing this I so dearly wanted to bring the reader close to show the child without sacrificing too much of the adult retrospective. A few weeks ago visiting my daughter I ‘read’ a little bit reciting it to her from memory and very suddenly when she did not expect it – to try it out . She responded ‘That’s good. What’s that? Something of yours?’

There are a couple of sections that were supposed to go into italics. Trouble is I might never have released it if I had not let go my hold when I did. I was getting fearful it wasn’t working, that I wasn’t working, that I might not present at the bar again. I tackled this for an hour or so Christmas Eve afternoon before I sent it to Emmjay. I did some slashing and burning, A number of features came to life especially the opening about the train, the Sunlander and the railmotor, describing the distinction, the railway crossing, the proximity of the house and the meaning of it to the lifestyle of the family.

The idea of communicating that by writing it has occupied my thinking for years and while the intent is not autobiographical, regardless, I am writing a descriptive image about a setting a lot of people know well, as well if not that location are familiar with living on railway lines and bus routes, transport corridors.

I endorse a reference I heard made to writing recently that it’s not easy. It is said over and over. It is not easy whatever anybody says. While to me the things I offer a reader to ‘see’ in the opening sentences remain crystal clear in my mind, the emotional journeys we have to deal with to arrive at a series of images that ‘work’ and entertain are so fraught with excitement and change, grief and loss, adventurous discovery. Very rewarding when people respond in a kindly and appreciative way.

May you have the best year ever on the horizon, Emmjay and all the crowd at the pub.

LikeLike

Hi Shoe,

A great read and have a good year. Thank you Shoe.

LikeLike

Thank you dear Gez. Kind regards this season to you.

LikeLike

Well, this kept me reading at a gallop until the end! Thank you, and festive greetings to you.

LikeLike

Thank you very much Yvonne. I am so pleased to engage your interest. Kind regards and festive greetings to you in return.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Shoe so wonderful to hear from you again and thank you for this wonderful piece. I enjoyed it very much. Merry Christmas to you and I hope you’re keeping well.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dear Algy few typos. I threw it onto the eds desk rough. I was mighty glad to get the gist down. I see I mixed up a few third persons and firsts lol. Thank you Algy. I am very glad you found enjoyment in it. Festive Seasons greetings. Thank you. Merry Christmas.

LikeLike