Story and Photograph by Neville Cole

The wind is still blowing my curtains horizontal. I walk back to the patio to find John and Justin quietly drinking strong, sweet Kenyan coffee. Do these African guys every sleep, I wonder. John pours me a cup without having to enquire whether I’d like one.

“We’re thinking of heading up to Koobi Fora this morning. Are you interested?”

“What’s Koobi Fora?” I ask.

“It’s a paleoanthropological archeological site,” Justin replies as if those multisyllabic words quite naturally roll off everyone’s tongue at seven in the morning; then, noting my blank expression, adds: “Leakey established a base camp there in ‘68. He set up a Kenyan search team called the hominid gang who discovered hundreds of fossil Hominins in the area. Mostly they found Homo habilis, homo rudolfensis, and homo ergaster but they discovered Australopithecus remains up there as well. It a very important site paleoanthropologically speaking.” By now I could tell these two African boys were enjoying themselves at my expense.

“Let me have a cup of coffee before you try to explain any more of this,” I moan. “It too early for all these fucking big words.”

Justin and the Frenchies are flying up to shoot some big scene for their documentary so I thought we might as well go along to check it all out.”

“You can see the movie being made and commune with the ancients at the same time,” Justin adds, sipping slowly on the thick, black liquid in his cup. “We’d take you in the helicopter with us but they are carrying all kinds of shit with them today: wave riders, ultralights, hang gliders…the entire crew, some local Turkana hands to set everything up and, of course, all the models and Cristo.

“Cristo?” I repeated.

“That’s the name John came up with for our new mysterious, wandering friend. It was getting tiresome last night continually referring to him as friend or stranger or bearded one.”

“I decided his full name is Jesus Cristo,” John added with a cynical snort. “He’s our most glorious existential messiah.”

“Anyway,” Justin continued, “You should come up to Koobi Fora with John and check it out. It’s going to be crazy.”

I am not one to want to miss crazy, so naturally I agree to go along.

“Great,” said John getting up from the table. We leave in about an hour and don’t worry about the costs; we’ll figure it all out when we get back to Nairobi.”

The flight to Koobi Fora took us all the way to the very tip of the Jade Sea. Here the landing strip is not only perpendicular to the prevailing wind but also covered in a three to twelve inch layer of loose blowing sand. Twenty-five feet above the ground we drop suddenly out of the sky and bounce violently to a rapid stop. “Wow!” John screams. “Lucky we didn’t snap the landing gear with that one! I only hope we’ll be able to lift up out of this quicksand later today.”

The ubiquitous African buggy picks us up at the strip. We see that the French crew and their small army of Turkana production assistants have arrived before us. Out of the enormous Russian helicopter has poured a mountain of equipment and that small army of Turkana production assistants. They have set about transforming the badlands landscape into a fully-fledged movie set. The first order of business it seems was to establish a base camp complete with a craft services tent and a hair and make-up station where the models will apparently to undergo some kind of prehistoric makeover.

In the distance I can just make out Justin and Cristo helping to lug two hang gliders to the top of an extinct volcano cone. Michel is talking to a couple of crew members who are busy constructing an ultra-light that will be rigged with a mounted camera. By the lake, I see a buggy unloading wave riders into the water. Jean is discussing the sequence of shots with the DP while grips set up two main cameras and and an array of reflectors. Everyone has a job to do but us.

“I’ve talked the driver into taking us down to the fossil fields,” John says tossing me a bottle of water he has snagged from craft services.

“I thought these were the fossil fields.”

“This isn’t where they find all the hominids,” John says already loping his way back to the buggy. “But Chongwe says he can take us to them.”

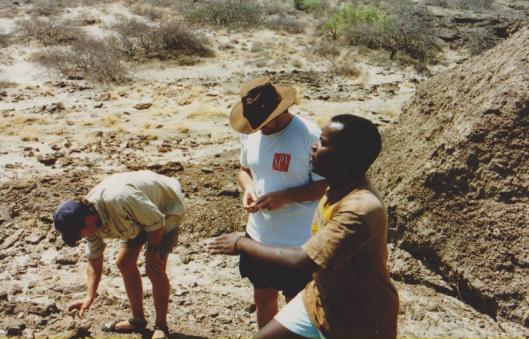

Our driver, Chongwe tell us he has worked at Koobi Fora for nearly half his life. As he drives us down the long, winding, rutted trail to the fossil fields he explains that searching the area for fossils has become his life’s work.

“Did you know Kamoya then?” John asks.

“Oh yes,” Chongwe smiles. “Mr. Kamoya is one of my most dear friends. I was one of the hominid gang. I helped Mr. Kamoya find Turkana boy. I was only a boy myself at the time.” Later John would explain that Kamoya Kimeu, is one of the world’s most successful fossil collectors. Kamoya worked with the Leakeys and is credited with making some of the most worlds most significant archaeological discoveries. The “Turkana Boy” Chongwe referred to was an almost complete Homo erectus skeleton found nearby in 1984.

As we trudge along the trail, Chongwe explains that, after the rains each year, the area is awash with rivulets and along each pit and gully new potential discoveries are exposed. That is when the team really goes to work. It has been a long time since the last rains; but it is still difficult to take a step without landing your foot on a piece of ancient history.

“Look at this!” Chongwe bends to down to pick up two, small, cone-shaped objects. “Crocodile teeth. This whole area was flooded by the lake about a million years ago.” John points out a curved fossil jutting out of gully which Chongwe says is a hippo jaw. I pick up shiny black rock about the size of a Swiss army knife.

“That is volcano rock. Over by the volcano we found an area where homo habilis made tools. That is knife for cutting fish. See? Fish bones everywhere.” We find fossils of every kind and size but our short excursion uncovers no identifiably human remains. Presumably those were all discovered soon after the last rainy season ended.

“I have done good work last season, my friends,” Chongwe smiles. “Everything there was uncovered I have found. Soon, the rains will come again and we will be out searching out for more ancient wonders.” We wandered with Chongwe for more than an hour. Slowly making our way up one gully and down the next like small children lost in a maze. Eventually we stop pulling up fossils and badgering Chongwe to identify each insignificant find. Instead, we find ourselves standing silently, trance-like, staring out over the post-apocalyptic sedimentary plain; all black lava, red claystones, brown siltstones, and grey sandstones, scattered with bone white fossils. None of us says a word for twenty minutes, maybe longer. Finally John, who has been unusually silent all morning, sidles over to me and whispers unconvincingly: “Well, this is almost as much fun as digging up graves. Let’s go see what the Frenchies are up to.” As we walk back to the buggy John is suddenly in the mood to talk again.

“So what do you make of that Cristo character?” he asks conspiratorially.

“Well,” I say, “he tells an interesting tale but I don’t believe much of it is true.”

“He says he’s been wandering out here for years?” John snorts. “I’ve seen backpackers who been out here for one week and they are without fail covered in welts and bites and their hair is a nappy mess. He looks like he’s just come from the spa. Did you see his hands? Not a callous on them. You are not going to wander through Africa the hard way and look like that. It is just not going to happen. If you notice, even the animals out here are covered in ticks and bites and scratches. It’s not a zoo out here. It’s the real thing! Anyway, we are agreed, right? He’s up to something. I just wish I could figure out what it is. Oh Jesus!” He says suddenly staring almost directly up into the sun. “Take a look at this, will you!”

Like Phoebus driving his chariot, the ultralight bursts out the glaring equatorial sun and buzzes directly over our heads. We scamper up the nearest hill to get a better view of the proceedings. From the top of the hill we can see the ultralight swooping down past a group of models positioned dramatically jet black lava flows. Each one stands, arms outstretched, with a thirty-foot trail of fluttering colored cloth blowing in the wind behind her. Narrowly missing the models, the ultralight turns and chases the wave riders along the lake shore; again each one carries a model clad in similar fashion to the lava sirens. Finally, the ultralight banks sharply back toward the volcanoes just in time to catch the two hang-gliders as they step off into the void and climb higher and higher into the piercingly blue sky.

“Whoa man!” says Chongwe who has scampered up the hill to join us. “This is some kind of show. Good thing we didn’t miss that!”

“What the hell is this documentary about anyway?” I wonder aloud. Nobody seems to know but we are all pretty sure it will look spectacular.

You’re one lucky son of a gun Nev. I’d give significant parts of my anatomy to be guided through the rift valley by Kamoya Kimeu.

This is a great yarn Nev. I find myself excited by each new installment as it’s posted but I can’t help finding myself waiting for some tooled up “technicals” to turn up in a modified Toyota HiLux fitted with a B.A.R.

Any chance?

LikeLike

There is a very good chance that an unusual vehicle or two will turn up soon. Especially when we head off to Uganda. I just have to find a way to stop having to do so much at work so I can find more time to finish the next darn chapter…

LikeLike

Obsidian. it’s a good word to say isn’t it, “obsidian”. Sort of sinister with a whiff of the occult. “Obsidian”.

The PreColumbian central Americans used obsidian knives to cut out the still beating hearts of their sacrifices. The iron stains in the limestone are still clearly visible at some locations.

The deal with obsidian is that being a kind of glass you can get the edge down to molecular thicknesses. Certainly much sharper than any metal or stone tool and speed of excision was the trick to getting at least one beat while the heart was in the shaman’s hand.

There was a tribe in western Victoria that held the rights to the only substantial outcropping of obsidian in SE Australia. It was traded as far as Queensland to the north and a single piece of Victorian Obsidian has been found in the Western Desert indicating the value placed on this material. The working detritus found at the quarry indicates that the locals reduced the raw material to blanks to reduce the carry weight and then traded “their” obsidian for others’ adhesive gums, skins and the usual range of barter goods including baskets, weapons and heavier greenstone axe blanks.

Just about every indigenous people on the planet with access to Obsidian has utilised the material for its superior cutting ability. It pops up all over the globe in trenches down to 200KYA.

There was also of course “The Obsidian Order”. For those with absolutely no meaningful life at all this link will fill you in.

http://memory-alpha.org/en/wiki/Obsidian_Order

LikeLike

Thanks, Warrigal,

The usual assumption by us post bronze/iron/titanium age folk is to assume that people without metals are technologically, therefore, intellectually inferior. Likewise we assume that only metals are really worth trading. Of, course there’s lots of evidence for first Australians trading all manner of things, from mosses and ferns (for medicine) to coal extracts (also used for medicines). There used to be sites not far from where I live where Awabakl people extracted light oils from coal.

‘Obsidian’ really does roll off the tongue!

Thanks again

LikeLike

One of my favourite Tom Waits lines is describing the moon as “A buttery cue ball rolling across an obsidian sky”.

Magic !

LikeLike

I know that I am boring, but I’ll write again..”Well written”.

I must take a lesson from you and start editing, or at least reading what I post!!

It’s not a zoo in here either. Boom boom!

LikeLike

yo

LikeLike

How do you decide the breakpoints Neville? It’s like watching a movie on a commercial TV station. Are you leaving space for ads?

LikeLike

Mostly the breakpoint is determined by the point of the story where I get too tired to keep writing for the night. You see, I mostly don’t get started until about 8pm and I find it hard to keep going much past 11:30 as I have to get up and go to work. One day I plan to put all the chapters together and do a final re-write without the commercial breaks…but while I am writing wouldn’t it be swell to attract some advertisers. This chapter of From Here to Nairobi brought to you by Tony’s Fish and Chips!

LikeLike

That shiny black rock is obsidian, volcanic black glass. I was fascinated by it as a child when I picked some up at a volcano in Oregon.

LikeLike

that’s right…now i remember it is obsidian. i still have it sitting on my shelf in the living room. i love to think of some hominid using my obsidian knife to cut up a fish.

LikeLike

This could be your lucky day Neville. I think Hung One on likes fish.

LikeLike