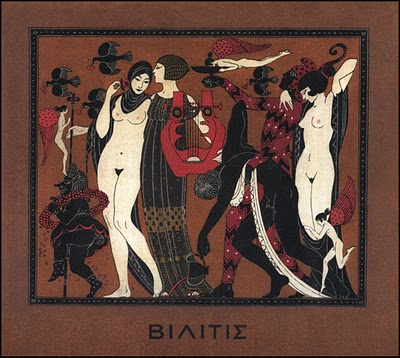

Some time ago Atomou felt the need to tell me what qualities he thought were necessary before one should ever attempt to translate anything from any other language into one’s own. I did not agree at the time, and still don’t. Since then I have briefly explained my disagreement, which is essentially the same as my disagreement with the orthodox dogma of the roman catholic church… the rigidity and inflexibility of orthodoxy is too limiting and rigid in itself at the same time as it refuses to allow the possibility of new interpretations. I did not, however, offer a full critique of what I referred to then (and still refer to) as his ‘diatribe’ on the art of translation; and I shall still refrain from doing so, however, as it’s been a long time since I’ve contributed anything, and as I’ve already ‘threatened’ to post my own translation of Bilitis, (which is the ONLY thing I have ever claimed to actually translate); it seems an appropriate time to post it; even though it risks being labelled ‘presumptuous’ or worse. You will note that I have not translated it from the Greek, but from the French language; the language of its author, who pretends instead to be the ‘discoverer’ of this ‘ancient’ text. I invite any and all piglets who feel interested enough to do so, to comment on my translation and the quality of my interpretation.

Perhaps, if I’m lucky, I may even draw Atomou back to the pub, if only to critique my work.

This first installment is my translation of Pierre Louys’ introduction to the ‘Songs of Bilitis’; I hope you will all enjoy

The Life of Bilitis

By

Pierre Louys

Translated from the French

by

David L Rowlands

THE SONGS OF BILITIS

A Lyrical novel

This little book about ancient love is dedicated respectfully to the young girls of the society of the future. (Pierre Louys)

Introduction: THE LIFE OF BILITIS

Bilitis was born at the beginning of the sixth century before our own era, in a mountain village situated on the border of Melas, to the east of Pamphylia. This country is dangerous and melancholy, darkened by deep forests, dominated by the enormous mass of the Taurus mountain ranges; petrifying springs emerge from the rock into large saltwater lakes; the heights and the valleys are full of silence.

She was the daughter of a Greek father and a Phoenician mother. She seems not to have known her father, because he is not mentioned anywhere in the memories of her childhood. Perhaps he was even dead before she came into the world. Otherwise one could hardly explain how she came to bear a Phoenician name, which only her mother could have given her.

In this nearly deserted land, she lived a peaceful life with her mother and her sisters. Other young girls, who were to become her friends, lived not far from there. On the wooded slopes of the Taurus range, shepherds grazed their flocks.

In the morning, at cockcrow, she rose, went to the stable, to water and milk the animals. During the day, if she wished, she could stay in the women’s quarters and spin wool. If the weather was fine, she could run in the fields and play with her friends the thousand games about which she tells us.

Bilitis had an ardent piety regarding the Nymphs. The sacrifices she offered were almost always for their spring. Often she even spoke to them, but it seems that she never saw them, to the degree that she recounts with veneration the memories of an old man which otherwise would have been surprising.

The end of her pastoral existence was made sorrowful by a love affair which we know a good bit about because she spoke of it at length. She stopped singing about it when it became unhappy. Having become the mother of a child whom she abandoned, Bilitis left Pamphylia, under mysterious circumstances, and never dreamed again of the place of her birth.

We find her again at Mytilene where she had come by the sea route along the beautiful coast of Asia. She was scarcely sixteen years old, according to the conjectures of M. Heim, who plausibly established some dates in the life of Bilitis, taken from a verse which makes allusion to the death of Pittakos.

Lesbos was then the center of the world. Halfway between beautiful Attica and the ostentation of Lydia, she had as her capital, a city more enlightened than Athens, and more corrupt than Sardis: Mytilene, built on a peninsula in sight of the coast of Asia. The blue sea surrounded the town. From the height of the temples one could distinguish on the horizon the white line of Atarnia, which was the port of Pergamus.

The streets, narrow and crowded by the resplendent multitude dressed in multi-colored fabrics, tunics of purple and hyacinth, cyclases (a kind of sleeveless surcoat)of transparent silks, bassaras (a type of mantle or great-cloak) dragging in the dust stirred up by yellow shoes. The women wore large golden rings strung with rough pearls in their ears, and on their arms massive bracelets of silver roughly carved in relief. Even the men had shining heads of well-coiffed hair. Through the open doors could be heard the joyful sounds of instruments, the cries of the women, and the noise of the dances. Pittakos, who wanted to give a bit of order to this perpetual debauch, even passed a law which forbade flute-players who were too tired being employed in the nocturnal festivities; but this law was never severe.

In a society where the husbands are so busy at night with wine and the dancers, the women were inevitably forced to reconcile themselves to find among themselves some consolation for their solitude. with the result that they softened to those delicate amours, to which antiquity has already given their name, and which they maintain; what they thought of men was more true passion than faulty research.

Sappho was still beautiful. Bilitis knew her, and she speaks to us about her under the name of Psappha which she used in Lesbos. Undoubtedly this was what made this admirable woman, who taught young Pamphylians the art of singing in rhythmic phrases, preserve for posterity the memory of these dear beings. Unhappily Bilitis gives little detail about this figure which is today so poorly known and this is cause for regret because the least word touching the great Inspiratrice is precious. In revenge she has left us some thirty elegies, the history of her own friendship with a young girl of her own age who she names Mnasidika, and who lived with her. Already we know the name of this young girl from a verse of Sappho’s where her beauty is exalted; but the name was doubtful, and Bergk was near to thinking that she was simply called Mnais. The songs one reads further prove that this hypothesis must be abandoned. Mnasidika seems to have been a small girl, very sweet and very innocent, one of those charming beings who have for their mission to let themselves be adored, so much more cherished are they that they make less effort to merit that which is given them. Love without reason lasts longest; this one lasted for ten years. We shall see how it was broken off through Bilitis’ fault, whose excessive jealousy failed to understand the least eclecticism.

When she felt that nothing was left for her in Mytilene except unhappy memories, Bilitis made a second voyage: she went to Cyprus, a Greek and Phoenician island like Pamphylia herself and which must have often reminded her of her native country.

So it was that Bilitis recommenced her life for the third time and in a way of which it would be more difficult to make admission if one has not yet understood at which point love became a sacred thing among the ancient peoples. The courtesans of Amathonte were not like our own, creatures in disgrace, exiled from all worldly society; they were girls from the best families in the city, and who thanked Aphrodite for the beauty which she had given them, and consecrated in service to her cult this recognized beauty. All the towns which possessed, like those of Cyprus, a temple rich in courtesans had in the regard of these women the same respectful care.

The incomparable history of Phryne, which Athena has transmitted to us, will give some idea of a real veneration. It is not true that Hyperidas needed to go naked to persuade the Areopagus and nevertheless, the crime was great: she had killed. The orator only tears the top of his tunic and reveals only his breast. And he supplicates the Judges “not to put to death the priestess and those inspired by Aphrodite”. On the contrary the other courtesans went out wearing clothing of transparent silk through which may be seen all the details of their bodies. Phryne was costumed so that even her hair was enveloped in great pleated vestments whose grace the figurines of Tanagra has preserved. No-one, if it were not her friends, ever saw her arms, nor her shoulders, and never would she be seen in the public baths. But one day something extraordinary happened. This was the day of the feast of Eleusis, twenty mule persons, who came from every country in Greece, were assembled on the beach, when Phryne advanced close to the waves: She removed her clothing, she undid her girdle, she even removed her under-tunic, “she let down her hair and entered into the sea”. And in this crowd there were Praxiteles, who after this living goddess drew the “Aphrodite of Cnidus” and Apelle who half-lived in the form of his “Anadyomene”. Admirable people, in front of whom beauty could be displayed nude without exciting laughter or false shame [fausse honte].

I would like this history to be that of Bilitis, because, in translating her Songs, I was seized by a love for the friend of Mnasidika. Without doubt her life was also totally marvellous. I regret only that I have not spoken further and that the ancient authors, those at least we have surveyed, are so lacking in information about her. Philodemus, who plundered her twice, doesn’t even mention her name. In default of pretty stories, I pray that one would really like to content oneself with the details which she gives us herself on her life as a courtesan. She was a courtesan, that is undeniable; and even her last songs prove that if she had the virtues of her vocation, she also had its worst weaknesses. But I do not wish to know only her virtues. She was pious, and even practicing. She lived faithfully at the temple, such that Aphrodite consented to prolong the youth of her purest worshipper. The day she ceased to be loved, she stopped writing, she says. Nevertheless, it is difficult to admit that the songs of Pamphylia were written in the period they were about. How was a little shepherdess from the mountains able to learn how to scan her verses which depended on the difficult rhythms of the Aeolian tradition? It seems more plausible that, on growing old, she could no longer sing for herself the memories of her distant childhood. We know nothing about this last period of her life. We do not even know at what age she died.

Her tomb was rediscovered by M G Heim at Palaeo-Limisso, beside an ancient road, not far from the ruins of Amathonte. These ruins had virtually disappeared for over thirty years, and perhaps the stones of the house where Bilitis lived today pave the quays of Port Said. But the tomb was underground, according to Phoenician custom and it escaped tomb-robbers [voleurs du tresor]. M. Heim penetrated a narrow shaft, filled with earth, at the bottom of which he encountered a walled door which he had to demolish. The cavern, spacious and low, paved with flagstones of marble, had four walls lined with a veneer of black amphibolite, where there were graven in primitive capitals all the songs which we are about to read, as well as three epitaphs which decorated the sarcophagus.

It was there where reposed the friend of Mnasidika, in a large coffin of baked earth, under a cover modeled by a delicate statuary which was figured in potters clay, her death-mask: her hair was painted black, the eyes half-shut and lengthened with pencil as if she were living and the cheeks artfully adorned with a light smile which emphasized the lines of the mouth. Nothing more would ever be said by these lips, at once clear and well-defined, soft and fine, united the one with the other, as if they had drunkenly come together. The celebrated traits of Bilitis were often reproduced by the artists of Ionia, and the Louvre Museum possesses a baked-earth tablet from Rhodes which is her most perfect monument, after the bust by Lanarka.

When the tomb was opened, she appeared in a pose with one hand piously arranged, twenty-four centuries previously. Vials of perfumes were hanging from earthen pegs, and one of these, even after such a long time, still smelled sweet. The polished silver mirror in which Bilitis saw herself and the stylus which had traced the blue on her eyelids were discovered in their proper places. A little nude statue of Astarte, a relic never so precious, keeping perpetual vigil over the ornate skeleton and all her jewels of gold and white, like snow-laden branches but so soft and fragile that at the moment they were gently touched they turned to dust.

PIERRE LOUYS

Constantine, August 1894.

Jolly good. I think. Too highbrow for me though, T2. Ilike cops & robbers, with a bit of soft porn 🙂

LikeLike

Wait ’til you read the poems, Funston… no cops & robbers, but maybe just the teensiest morsel of… well… maybe not soft porn, but perhaps a little mild eroticism here and there.

Oh! Hang on there is that bit about the maenads in the forest and what they do with their purple… oh but I shouldn’t spoil it for you…

🙂

LikeLike

I feel it very well translated. The structure remains simple and easily understood. Your French must be very good. It kept my interest throughout the piece and you stayed clear of unnecesary flourishes and decorations. Well done Asty.

LikeLike

Merci bien, mon ami! Of course, it’s much easier to translate from French into English than the reverse (for a native English speaker!) The songs, when read sequentially give the life-story of Bilitis in episodic glimpses; to my mind, together, they comprise a wonderful recreation, however imaginative, of ancient Lesbos.

🙂

LikeLike

The story reads well, it flows nicely, it does not read like some badly translated books read, awkward…

Not so long ago, I bought a translated version of a well-loved Swedish master piece. I had always loved the book but could not read the English version….Gerard persisted but even he finally said: How poorly written! Yes, poorly indeed, but only the translation…

Well done, asty.

LikeLike

Thank you Helvi… glad you like this intro; I think you’ll like the ‘songs’ when I post them. I’ll probably post about half-a-dozen at a time; they’re only short poems really.

🙂

LikeLike

…my grammar lacks something because I was rewriting the final sentence to say something about the story and the rhythm respectively… in a nutshell I think the effect is great beauty. Thank you..

LikeLike

Even in the act of translating these songs, ‘Shoe, what struck me about them was what great beauty Pierre Louys had created using only the simplest of language and phraseology… ‘elegant’ is the word which comes to mind… elegant in its economy of words for such vividness of description.

🙂

LikeLike

asty, I am interested in the date of the French original of this translation and can see the time frame and its students. That interests me. It has its own charm. I like very much that I am taken into the period you translate from. I would never have been able to access that. It gives me an extra dimension and understand I am appreciating your translation. If a critic wants to offer a comment further that suggests you have it wrong I will read that if it appears. I wil appreciate whatever is said from the perspective I am an intelligent and creative reader. Particularly it is wonderful to know the source and feel oriented.

The story and the rhythm of the language is beautiful.

LikeLike

Thank you for those kind words ‘Shoe; I’m sure that you too will enjoy Bilitis’ songs when I post them; even though they are a hoax, I find them to have a rare kind of beauty, if judged as works of imaginative fiction and their ‘hoax’ nature forgiven.

;).

LikeLike

Hi Asty.

I had trouble translating French menus into English food, so I can’t make an informed assessment on that score, but I can say that my interest was aroused (if that’s the correct phrase) by this introduction. Looking forward to the songs.

I’m interested in the notion of the work being a hoax. I understand the thing (a hoax) to be something of a cruel joke, supposedly defensible on the basis that it pricks some puffed-up expert’s balloon. Tell us more about this one.

LikeLike

I really wish I knew more, Therese… I’ve been meaning to investigate that for some time… been a bit slack, I guess… Maybe I’ll do a bit of digging and see what I can find on the subject… It might make a nice additional article.

Speaking of hoaxes though, lately I’ve been looking at some of the wierder kinds of movie one may download from youtube… Did you know there are people out there who believe the moonlandings were faked; that aliens have a base on the moon; that the earth is hollow and inhabited by alien life-forms; that ancient aliens left the seeds of Egyptian culture 6 or 7 millenia before the Great Pyramid was built… to be a beacon for aliens from a distant galaxy, of course!

I’ve become a little fascinated by some of the far-out crap that people are prepared to believe… I suspect much of it has to do with the so-called ‘church of scientology’, but haven’t quite fixed its main epistemological focus yet. But it’s gonna take a while to watch all the footage I downloaded! I sense an extraterrestrial article in the offing…

🙂

LikeLike

What about this for weirdness: The Labor Party believe that if you keep taking from the middle class, it somehow improves the balance of payments – foreign revenue. Weird huh?

LikeLike

Or, Funston, how about those neo-Con parasites who think that as long as they personally are richer than Croesus, their countries MUST be doing okay, even though they avoid paying tax like the plague… and who believe that it is more important for them personally to be obscenely wealthy than it is for normal people to have homes or eat…

😐

LikeLike