Story and Photographs by Neville Cole.

“You’re doing much better today, old man,” John chirps into the headset. “Your cheeks are positively rosy. For a while there yesterday I was worried I’d offered a ride to a zombie. That’s how bloody green you were! You know, what I mean?” I have to admit I know what he means. “Of course,” he continues, ever happy to fill any void with the sound of his own voice, “it’s always smoother over the lake than over the Rift so if you were at all queasy today I’d have to poke some serious fun at your expense. Anyway, I am glad you look human and not like some frightful Jade Sea monster.”

I look down at Lake Turkana. It is an almost iridescent shade of jade. In fact, both the water and the landscape are glowing in saturated light. “Golden time,” I note wistfully, “that wondrous hour just before dusk when the Earth from horizon to horizon is bathed in shimmering rays of light.” I have worked with enough camera-types to understand the rapturous delight that particular profession holds for this brief moment in time. No matter how long and exhausting the day may have been up to that point, when golden time hits every professional that wields a camera suddenly attacks the day with renewed vigor. I feel my energy and spirit rise just contemplating it.

“It’s quite spectacular, isn’t it? Hey!” John says excitedly. “Did you see Out of Africa? See if you can remember this scene.” He dips one wing and our little Cessna obliges by wheeling toward the edge of the lake. “Keep looking straight down,” he says like a parent warning a child not to peek at his Christmas presents. “Focus on the water. Don’t look around. Believe me, you will write about this in one of those stories of yours one day.”

Obedient as ever, I stare at the shining jade mirror below and John guides us lower and lower and closer and closer to shore. All I see now are glowing red sand, burgundy brown clay and glistening green zipping past in a blur of animated motion. “I wish I had a camera that could do this justice!” I say. “It’s like a gigantic work of art!”

“Keep watching,” he says. “Here comes the pièce de résistance.” Suddenly the whole scene bursts open with an explosion of dazzling pink as just below us several thousand flamingoes are spreading their wings and taking flight in unison.

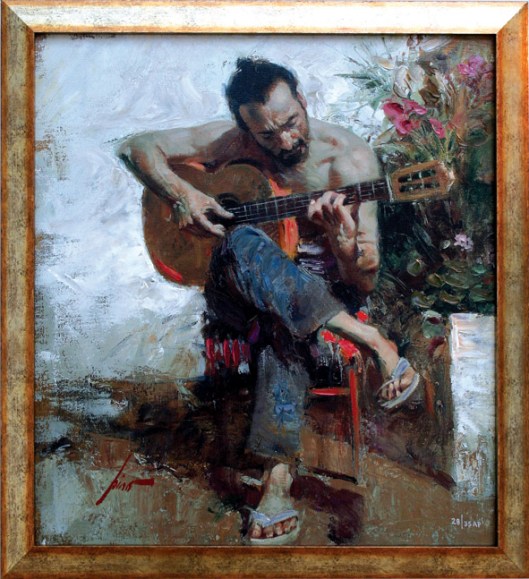

“How’s that for a painting, man? Very impressionist, don’t you think? Would you say that is a Manet or a Monet?”

“It’s a Turner!” I yell back into the headset with genuine excitement. “Wait, maybe a Van Gogh! Wow!” I add incapable of adding any further perspective but nonetheless still entranced by the display.

“Exactly,” John says smiling with pure, unadulterated glee. We fly on in wordless bliss all the way back to Loyangalani.

Dinner tonight is a quiet, even subdued, affair. I can’t tell if this is a result of general exhaustion or whether the absence of a certain gypsy is to blame. Apparently, immediately after returning from Koobi Fora, Cristo thanked everyone for their kind generosity and wandered off in the general direction of the El Molo village. The energy of the whole crew seems to have disappeared with our absent friend. Apparently no one has any interest in anything much tonight, especially philosophy. Jean and Michel are the only people talking at all and their voices barely rise above a whisper. They are speaking in French so I can’t say for sure what they are talking about; but from what I can gather they are both in agreement that it’s time soon to break camp and move on.

After dinner I move on myself: out to the pool to float on my back and stare at the stars. The stars in Africa are bigger and brighter than anywhere on the planet; at least they seem so tonight. Somehow, far from being uplifted by this recognition I lapse into melancholy. Doubts I thought I had left far behind creep back into my conscious thought. “What the hell was I thinking? Why did I come here? What am I trying to prove? What am I going to do when the money is gone? What will I go back too? What exactly is the point? But my lonely sadness is fleeting. Exhaustion, I tell myself, can play tricks on the mind that most drugs don’t come close to matching. I determine that all I really need to do is sack up and accept that the future has not happened and that anything can change and most likely will. “You are in fucking Africa, man!” I blurt out angrily. “If you don’t enjoy every moment of this fucking trip I am going to personally find a way to kick yourself in the arse!” I can get pretty tough with myself sometimes; especially when I am acting like an idiot. I drag myself back to my tiny cot and resolve to make the most of the next day.

The next thing I see is the John Allen’s somewhat bloodshot eyes staring intently in to mine.

“Neville,” he says, “Oy! Wake up, old chap. I need to speak to you.”

“Eh, wha?” I slur.

“Good you’re awake,” he answers plopping down dramatically. “Here’s the deal. I got to talking with one of the girls last night and found out the crew is wrapping up here tomorrow. Anyway, the girls want to take a quick side trip down to the Seychelles for some R and R. and the thing is…well, there’s not enough room for you.”

“Huh? Huh?” and repeat with growing conviction and a hint of panic.

“But look, I’ve worked it all out. Here’s the plan. Jean and Michel have agreed to take you with them tomorrow to Uganda to see the gorillas. Then, I’ll be back in a day or so with the girls and meet you there.”

“Uganda?”

“I know,” John continues. “Isn’t that a stroke of luck? A free trip to Uganda in a Russian helicopter! Your story is getting better by the hour, my friend. Oh, and I set you up today too! Kwaku is going to take you fishing. I wish I could come with you, but I can’t. I have to fly to the Seychelles. Ok. Well, I’m off! You should probably get up. Kwaku doesn’t like to get out on the lake too late. You are going to have such an amazing experience! He’s been fishing these waters longer than anyone.”

“Fishing with Kwaku?”

“I know. Can you believe it? Got to go now,” John says already heading to the door. “See you in Uganda in a few days. Cheers.”

Ever have one of those moments your brain forgets to send any impulses to any part of your body and you find yourself in stasis? That’s me when John walks out that door. For five minutes I stare unblinking straight ahead expecting him to walk back in and say “Just joshing” or “april fools” or even “gotcha sucka!” But no, John is serious. He is taking a group of supermodels to an island paradise and I am flying to Uganda in a Russian troop carrier; that is, after I spend a day sitting in a tin boat on a lake under the equatorial sun with an old guy who works in the kitchen. Wow, I can’t believe my luck.

Kwaku, smiles me a huge, toothy smile when I finally stagger out to the breakfast table. “We are going on the lake today, bwana. Kwaku will show you how to catch the biggest fish on the lake. Then we cook it for dinner. You ready to go, bwana?”

“Neville, Kwaku. I am Neville. Yes, I will be ready in a minute. I just want some coffee and some eggs first.”

“Eggs, yes eggs” Kwaku says getting to his feet. “You eat, bwana Neville. I will pack some lunch and beer, yes? Beer for the fish?”

“If that’s the way you catch them, Kwaku, by all means. Bring the beer.”

“We will catch a very big fish today. Biggest fish you have seen. You eat now then we will fish.”

Kwaku is positively giddy about getting out on the lake. I guess he is close to sixty years old. He has no doubt been fishing here since he was a small boy; yet here is still genuinely thrilled to be heading out to drop a line. Is it just that his life is simpler than mine, I wonder? Or is it truer? All I know is that as I drink my coffee and chew on my eggs and toast I find his enthusiasm is contagious. I forget about John and the models and the white, sandy beaches and the suntan lotion and begin to look forward catching a really big fish. “What if I caught a 50 pounder?” I ask myself. How would I handle a 100 pounder? What is it like to land a fish like that?

When I see the boat we are to fish in I scale back my expectations. It is something between a canoe and a dinghy. “This is the charter boat that Wolfgang rents out?” I ask Kwaku.

When I see the boat we are to fish in I scale back my expectations. It is something between a canoe and a dinghy. “This is the charter boat that Wolfgang rents out?” I ask Kwaku.

“Oh no, bwana,” Kwaku says laughing. “Wolfgang left in his boat this morning. We will go in my boat. This boat is good luck, bwana. We will catch a big fish today. I climb perilously into Kwaku’s boat and help load in supplies. Along with the African camp lunches – which always seem to consist of a salami sandwich with lettuce, cheese and cucumbers, one boiled egg and one whole tomato – Kwaku hands me a large leather pouch full of water, a crate of already warm beer, a couple of hand lines, a landing hook, a bucket of fish guts, and some bait. I note that there are no life-jackets on board and only one oar. I settle into a position at the bow of the boat while Kwaku pushes away from the shore and primes the tiny, ancient outboard. He wraps his hand around the knotted cord and standing, but almost bowed in prayer, gives the starter a mighty yank. A cough is all the outboard is willing to offer in response. Another bow from Kwaku and then with one hand on the outboard for support he gives the engine another violent tug. Nothing.

“She is always a little stubborn in the morning,” Kwaku says smiling. “Just like a woman.” A half dozen similar unsuccessful start attempts and finally the engine gives an extra hiccup and then a sputter. Kwaku drops the starter rope, reaches for the throttle and revs the engine. I try to ignore the plume of black smoke that chugs out of the testy little engine.

“We are ready, bwana!” Kwaku yells above the whining outboard. “Hang on to your hat.”

“Please, Kwaku,” I call back, “stop calling me bwana. My name is Neville.”

Kwaku smiles but stares right past me out to the lake with his head tilted back as if he were trying to smell where the big fish might be. I turn around gingerly to look out at the lake myself. It looks entirely different from this angle. Instead of the bright jade coloring visible from the Cessna, the water here appears dark brown, almost brackish. The lake is also much larger from the vantage of Kwaku’s tiny boat. I remember reading that Lake Turkana is the world’s largest permanent desert lake and the fourth largest salt lake in the world; only the Caspian Sea, Lake Issyk-Kyl in Kyrgyzstan and the Aral Sea are bigger.

I am grateful that the wind is less strong this morning; but I am aware that as the day goes on and the land heats up the gusts will pick up as well. I wonder how Kwaku’s boat and my stomach will handle some afternoon whitecaps.

The shore recedes and far ahead I see the Central Island, which is actually an active volcano, emitting small puffs of white-grey vapor into the cloudless sky.

The shore recedes and far ahead I see the Central Island, which is actually an active volcano, emitting small puffs of white-grey vapor into the cloudless sky.

“Is it always smoking like that?” I call back to Kwaku. He smiles broadly again and laughs, clearly dreaming of that first fish. I see there is no point trying to communicate until the engine is shut down and start to internalize my thoughts. I tend to have a habit of falling into a trance whenever I find myself a passenger. I don’t like to talk on planes or trains or in automobiles when I am not driving. Instead, I pass the time alone with my thoughts in a dreamlike travel limbo. I am almost convinced that this literally makes the time pass faster. A form of time travel, I suppose.

As we power out to one of Kwaku’s favourite fishing spots, I begin, as I often do, to contemplate the history of my present locale. For centuries or so this watery expanse was generally known as Basso Narok, or Black Lake in the Samburu language. My guess is the Samburu never had the opportunity to see the lake from the vantage of a Cessna and so the idea of comparing the lake to jade never came up. The name Basso Narok was the most common name for many years because on the arrival of the Europeans to the area the Samburu were the dominant tribe. Each of the local peoples – the Samburu, Turkana, Rendille, Gabbra, Daasanach, Hamar Koke, Karo, Nyagatom, Mursi, Surma and el Molo – have names for the lake in their native tongues and these names were not always related to the color of the water. For instance, the Turkana call the lake anam Ka’alakol, meaning “sea of many fish”.

Some people will have you believe this lake did not truly exist until March 6th, 1888. That is the day Count Sámuel Teleki de Szék and Lieutenant Ludwig Ritter Von Höhnel, a Hungarian and an Austrian respectively, happened upon the lake while on a safari across East Africa. They immediately dubbed it Lake Rudolf in honor of Crown Prince Rudolf of Austria. Another sad colonial irony: a lake that had been a source of sustenance for generations of hominids going back 3 million years would not be actually be discovered until 1888.

The lake kept its European name throughout the colonial period of British East Africa up until 1975 when post-colonial president Jomo Kenyatta renamed it Lake Turkana, in honor, not coincidentally again, of the dominant tribe of 1975. To the victor go the spoils. Interestingly enough, fishing has never been a big part of traditional Turkana culture. In fact, many Turkana clans consider fish taboo. Perhaps, I tell myself the name, lake of many fish, was not meant as a particularly glowing commentary. In fact, only during colonial and post colonial eras did Turkana start fishing at all. Kwaku, it seems, is one of the first of his kind.

The engine cuts suddenly and the silence is immediate and shocking. “Here we are, bwana.” Kwaku says happily.

“Please Kwaku,” I say quietly, “call me anything but bwana. I’m a guest on your boat today, not a bwana.”

“Alright, my friend,” Kwaku says warmly. “Out here you are no bwana. We are just two mvuvi, two fishermen. Tutavua, we will fish, my friend. Perhaps Akuj will send us many big sangara. That is our name for the nile perch.

“I didn’t think Akuj approved of fishing,” I say as Kwaku tosses half a bucket of chum overboard.

“We Turkana are, what is that word Wolfgang says of us? Praggish?

“Pragmatic?” I offer.

“Yes, he likes to say the Turkana are a pragmatic people. Wolfgang says that is why we have become a strong tribe. Maybe that is why so many Turkana have become Christians. Why so many, like myself, have taken to fishing. Wolfgang seems to think this is sign we have forgotten the old ways. But I don’t see things quite this way. I am not so sure. I have always fished and I have always prayed to Akuj to bless my endevours. I know no other way to live. Is that pragmatic? Is that what he means?

“I don’t see anything wrong with seeking as much help as you can in this life, my friend. What you do is practical. If that is being pragmatic, then that is what I am too. We are two pragmatic fisherman today. And if Akuj wants to bless my line I will gladly accept his blessing.”

“In truth, bwa… Neville,” Kwaku says stopping himself. “In truth, I don’t think Akuj has much time to worry about whether we catch a sangara or not. He is busy with other things, I think. Like whether or not to break this drought soon.

We fish for some time in silence. The occasional gust of wind in our ears and continual lapping water against the boat are the only noises in the whole world. Kwaku pulls out his tobacco and stuffs some into a pipe. He lights up and starts puffing away like the volcano on Central Island.

“Etaba? You smoke?” He asks proffering the pipe. I don’t smoke but that hardly seems the point. If I am to be a true mvuvi today, I should at least try a little. I cautiously take the pipe in hand. The etaba is pungent and sweet. I always seem to like the smell of tobacco so much more than the taste. Perhaps a lifetime of secondhand smoking has addicted me to the smell but it has never made me want to pick up the vice. I take in just the smallest hint of smoke but even that is enough to burn my lungs. “Mmmh…” I choke, handing the pipe back to Kwaku. “That is strong stuff.”

Kwaku laughs so hard tears are rolling down his cheeks. “You are no bwana, my friend!” he says happily. “No bwana has ever shared my pipe! And you don’t even smoke. You want beer?” he says already handing me an open bottle. “Maybe you want to wash that smoke out of your mouth?”

I have to admit that even a warm Tusker taste pretty good right now. Sitting in the middle of this ancient sea, with my ancient friend, with nothing to do but hold our lines and wait.

I notice Kwaku’s hands as he skillfully winds in his line to attach a fresh bait fish. They are weathered as rocks along the shore. Close to sixty years of line have run through those fingers.

“What is it like to catch a big sangara?” I ask. “Do they fight hard? Should I let out the line when it bites?”

“You will feel the bite” Kwaku says, “There is no missing it. It is better to let him run a little. Then, if you have a big one, you can wrap the line around the oar pin and we will go for a little ride. When he stops swimming, then we pull him in. If we get a big one we will work together.

“My hands are so soft. I hope I can be help to you.”

“There is some leather up front there. Wrap some around your hand and you will be alright. But, there is nothing around here today, I think. Let’s have some lunch and I think perhaps we should go on a little further if we have no bites soon.”

I am just finishing peeling my egg when I get the first bite of the day. The line digs firmly into my leather wrapped palm and I instinctively shove the entire egg into my mouth and grab hold of the line with both hands.

“Mmmuh…mmpfh!” I shout through my egg-stuffed pie hole.

“Is it a big one?” Kwaku asks excitedly. I nod my head vigorously trying desperately to bite and swallow the egg without dropping the line or the egg.

“Tie it off,” he says. “Tie it to the pin! Let’s ride him out?” I quickly wrap the line around the oar pin then immediately reach to pull the uneaten portion of my egg out of my mouth.

“Wow! That was some bite!” I say “It nearly dragged my arm off! How long do you think it will be before he gets tired?”

“I think he is already tired, my friend,” says Kwaku laughing yet again at my expense. “We are not going anywhere.”

“Well, there’s two of us in the boat,” I say. “Maybe we are too heavy to pull.”

“Pull in your big sangara, Neville.” Let’s see what you have.

Kwaku’s suspicions are correct. It is not a big sangara but a modestly sized tilapia. Nothing that will feed the village but enough to make a tasty meal for one happy mvuvi. Kwaku throws the fish into a net and hangs it over the side of the boat.

Kwaku’s suspicions are correct. It is not a big sangara but a modestly sized tilapia. Nothing that will feed the village but enough to make a tasty meal for one happy mvuvi. Kwaku throws the fish into a net and hangs it over the side of the boat.

“This is not a good spot,” Kwaku says rapidly pulling in his line. “Let us move to the deep water.”

The wind and waves are picking up but I am at least encouraged that the outboard starts up after only three tries out here. In all honesty, I feel quite proud of my catch. Indeed, on any other occasion I would have felt I’d already had a spectacularly successful day fishing. Kwaku, of course, does not have the same respect for my catch.

“When we get to the deep water” he yells to me over the outboard, “you can use that little fish to catch a proper one!”

I take the opportunity to finish my sandwich and tomato. I also reach for another warm tusker. How big a fish could we possibly catch in this thing anyway? I recall a photo of a record nile perch that nearly topped 500 pounds. Surely a fish like that would drag this flimsy boat to the bottom of the lake. Photos from the Oasis Club’s glory days show numerous fish pulled out of the lake that were bigger than the fishermen who reeled them in. Perhaps I am still light-headed from Kwaku’s tobacco but I am only now starting to wonder if coming out here with no radio, no life-jacket and one oar was such a good idea in the first place.

Kwaku cuts the engine for a second time and I can no longer hold back my curiosity. “What the biggest sangara you’ve ever caught, Kwaku?”

“Once,” He says happily dumping the rest of the fish guts overboard, “I caught an old fish so big I could hardly fit it in the boat with me. I had to sit on its head all the way home!”

“I see,” I nod, “and did you catch that fish out here in the deep water?”

“I see,” I nod, “and did you catch that fish out here in the deep water?”

“No,” he replies matter-of-factly, “I caught him close to shore. I don’t know what we will do if we get one like that all the way out here. This old boat might not make it back.”

I can’t tell for sure if he is kidding in that infamous deadpan African manner or if he really hasn’t considered the worst that could happen. The fates, I suppose have protected him out here for 50 years. Why would he imagine they would stop now?

For the next few hours we bounce around in the steadily growing wind and I find myself growing steadily more queasy. Much to Kwaku’s amusement, I have refused to bait up my tilapia. I tell him I plan to eat my meal-sized fish all by myself for dinner tonight.

We fish and drink on. Somehow the warm beer actually seems to be settling my stomach. Either that or I am just drunk enough not to care how much the boat is tipping. I see Kwaku checking the sun. I don’t have a watch on, but it is clearly late afternoon and Kwaku is starting to consider that we may have to turn back soon completely empty-handed; but before he can voice his concern his whole body lurches forward almost carrying him out of the boat. My beer, which was sitting on the seat next to me also lurches forward and immediately smashes at my feet.

“Oh my!” Kwaku yells. “Quickly, we must change seats! You come to this end and I will tie him off at the front of the boat. This is a big, old man sangara.”

I try to do as Kwaku has said but the beer and waves make shifting around quite a challenge. A piece of broken beer bottle cuts into my ankle as I make my first step.

“Ow, shit!” I yell.

“Keep moving,” Kwaku says firmly. “I must tie him to the bow. If I tie him to the oar pin he might tip over the whole boat. I continue to slide to the back, bloody ankle and all, only to be suddenly jerked off balance by a bite of my own. I end up sprawled in stern with my feet above my head still gripping the line in my left hand.

“Two fish!” Kwaku yells. “Well, this is a new story indeed!”

“I don’t think mine is too big.” I call back. “It feels like the last one. A big tug at first but nothing now.”

“Maybe they will make each other tired,” Kwaku says finally getting a chance to tie off his line. This time there is movement. I can feel Kwaku’s fish pulling us forward. I can do nothing but lie on my back and hold onto my fish for dear life. Kwaku makes his way back slowly to help me get back onto my seat. I try to pull my fish in but the line is cutting into the leather straps.

“Let me see your ankle.”

“It’s fine,” I say.

Kwaku is already removing his shirt. “Hold still. Let me see if I can stop the bleeding.” My leg wrapped, Kwaku turns his attention back to the tied off line. We are still being dragged slowly though the water. I feel the fight go out of my line and start to bring it in. A flash of silver appears on the surface about 15 meters behind the boat.

“Sanbura!” Kwaku calls out. “A nice size my friend, perhaps 40 pounds! Keep pulling let’s see if we can get it landed before mine gets tired. Sweat is dripping from my brow, the t-shirt around my ankle is spotted with blood. I begin to wonder when the tears will start to flow. I pull on the line while Kwaku takes up the slack, winding the line back onto the reel. I take note that I must do for the same for him as he tries to land his fish.

When I finally get the sanbura near the boat, Kwaku grabs the landing hook and expertly snags the great fish behind the gills and in a single movement hoists it aboard. It is probably three feet long and the biggest fish I have ever caught. Kwaku does not stop to admire my catch; he, quite clearly, has bigger fish to fry.

“He is still pulling,” Kwaku says amazed. “This is a giant. Maybe not a he, after all. Maybe a she. Your little fishies mother perhaps. Come now, take my reel. I’m going to try and urge her in this direction.”

Kwaku loosens the line from the bow and it immediately starts to slide through his left hand cutting into his fingers. He already has the line wrapped around his right hand and reaches back with his left.

“Leather,” he cries out. “Quickly wrap my hand.” I remove the wrap from my hand and strap it around his. Kwaku places both feet against the hull and leans back taking in the line a few inches at a time. I grab his reel and take up the slack as I had seen him do for me. This continues for perhaps 20 minutes before Kwaku wraps the line back around the bow and sits back to rest. I hand him his leather water pouch which he raises to his mouth.

“This is a big, strong fish, my friend. In truth, we should be heading in but I would very much like to land him. Are you willing to let me try?

“Of course,” I say. “Would you like me to try pulling for a while?”

“No, this one is mine,” he replies. “You just be ready with the hook when I get it close.”

Kwaku goes back to landing his fish and I note another splendid golden time is upon us. What a lovely shot this would be. Kwaku’s old, scarred, but still quite remarkably muscled torso bent forward with his arm raised and the line pulled sharply to the water while the leather wrap trails straight down forming an arrow pointing heavenward toward the setting sun.

Again, the familiar flash of silver appears in the water; but this fish even in the quickly fading light is clearly much larger than mine.

“Oh my god, Kwaku! We’re going to need a bigger boat! It’s never going to fit in here. What do we do?”

“We will do like the fisherman in that Hemingway story Wolfgang likes so much. Tie it to the side of the boat.”

“Are you serious!” I yell. “That didn’t work out so well for Santiago, if you recall.”

“We will be fine. Akuj is with us. How else do you explain two fish like this taking our lines are the same time? Akuj is the source of all power. No challenge is impossible to Akuj. He will show us the way.

I’m trying to trust in Akuj but my faith is as of a mustard seed. The sky is getting dark and my mvuvi friend is intent on trying to land a fish several feel longer than the boat we are sitting in. This is obviously the catch of his life and the rush of adrenaline he is experiencing leaves no room for fear or doubt. The fact that we are in the middle of the black lake with one oar and a dodgy outboard is of no consequence to Kwaku. Nothing matters now but beating the samara.

“Get the hook,” he calls out suddenly, “I’ve got him.”

“What do I do with it?” I cry. I can’t lift that bloody thing!”

“Catch his gill and hold him up to the boat while I get a rope.”

The likelihood that I can hold this several hundred pound sea creature against the boat for long is mircoscopic; but Akuj be praised, I lift the hook and take an almighty swipe at the great fish. Unfortunately my swing glances harmlessly of the monsters skull and only succeeds in inciting the beast into thrashing around and nearly knocking the two of us into the murky depths.

“Again, Neville! Aim for the gills. Pull him in!”

This time I swing with less force and more direction and manage to lodge the barb into the fleshy meat of the gills. My blow doesn’t kill the fish but seems to take away his will to fight, at least momentarily. As soon as I make contact Kwaku grabs the anchor line and wraps the rope several times around the giant’s tail. Then he attaches a second line the landing hook and ties it tight to the bow. The big fish lies quietly in the water like a second hull. I look to Kwaku and find it is he who is crying.

“This is the day I have dreamed of all my life. Now what shall I do?”

“Well, for one thing we need to get this thing to the shore. We need to have some other people see this so we can be sure we aren’t dreaming.”

“Good thing for us there are no sharks in anam Ka’alakol.”

“Yeah,” I reply. “That’s all we need about now.

Kwaku’s eyes still full of tears. “Thank you, my friend,” he says taking my arm. “Without your help I never would have caught him.”

“You are very welcome,” I reply more than a little distracted by the disappearing light. “Now how about you watch that fish of yours and I’ll see if I can get this little outboard started get us back to shore.”

I have never heard a sweeter sound that that engine starting up after the first pull and all the long slow crawl back to shore I think of nothing but how nice it will be to be back on dry land with an ice cold beer. Thankfully the fish is barely moving. Towing it is like dragging a tree trunk through the water. The little engine is puffing and whining in frustration; but, like Kwaku and I, it refuses to quit.

Fortunately, the lights of the Oasis Club stands out like a beacon of hope and guiding the boat to shore is one of the simpler things I have done all day. Kwaku is laying flat on his back with one hand holding the landing hook and the other gripping the opposite side of the boat. I can’t help but note he looks like a certain messiah of which we have all heard tell. “Papa Hemingway would have a fine old time with that image” I laugh. I also can’t help but start thinking about bloody John Allen who is no doubt sitting with supermodels at a beach bar in the Seychelles about now. “Oh well,” I tell myself, “I wouldn’t have missed this day for all the supermodels in the world. This is truly the experience of a lifetime.”

Kwaku sits up suddenly with a look of real concern on his face. He indicates that I should stop the boat. I turn back the throttle to a low idle.

“I just remembered something, my friend.” he says quite seriously. We may not have sharks here; but we do have crocodiles. You better let me take us into shore.”

NEXT UP: NEVER PISS OFF A HIPPO, MY FRIEND