Theseustoo

As Harpagus predicted, the battle opened with a cavalry charge from Croesus’ heavy lancers. But Cyrus had seized the initiative and moved first, thus forcing the Lydian lancers to move before they were quite ready and this upset their timing; thus their battle-line was fairly ragged even at the start of their charge, so it was unable to gain the momentum a massed charge really needs for maximum impact. Then, as the two armies closed together at the gallop, the Lydians were thrown into confusion as the horses neared the enemy and caught sight of the camels. As these ugly beasts now charged towards them, many of Croesus’ cavalrymen were thrown to the ground by their horses as they panicked and reared in their frenzied attempts to escape. As soon as the Lydian cavalrymen were thus thrown to the ground they were swiftly dispatched by Persian spearmen, who followed the camels very closely.

Confusion increased to absolute chaos as the armies drew close enough for the horses to smell these alien and terrifyingly ugly quadrupeds which were even now bearing down on them. Even those Lydian horses which had not thrown off their riders turned round and galloped away as fast as they could the moment they caught sight or smell of Cyrus’ camels, heedless of both their riders’ commands and their whips as they wielded them furiously in their futile efforts to restrain their steeds. The wisest of the horsemen among them gave their mounts their head and just hung on for dear life, until their mounts ran out of breath.

However the best of Croesus’ cavalrymen instantly understood what was happening and quickly leaped off their horses before they too were thrown, and engaged with the Persians on foot. But it was too late; on foot they had lost all impetus and the riders on Cyrus’ camels bore heavily down on them with their long, bronze-tipped lances; and, since most of their comrades had either been thrown from their horses and killed, or else had given their steeds their head and fled, they were far too few; all semblance of battle formation had been lost in an instant and they were easily slaughtered. Harpagus’ stratagem had been very effective, completely neutralizing the impact of Croesus’ cavalry charge; and when the rest of Croesus’ forces saw the slaughter that was now being done to the fleeing remnants of the scattered cavalry, they immediately fled back to the safety of Sardis’ high city walls, while the Persian host encircled the town well beyond bowshot, and prepared themselves to lay siege to the city.

*** ***** ***

Croesus took off his heavily-mailed leather gauntlets and threw them onto the table as he strode into the war-room with Sandanis and his other officers in tow. The gates of Sardis had been firmly barred behind them and archers had been stationed at the walls to keep the enemy at a distance. Croesus looked tired and weary as he spoke to his officers: “Sandanis, we must send more heralds to all of our allies; especially to the Spartans; they are to inform them that we are already besieged; and that they are not to wait for spring, as we had planned, but to come immediately!”

“At once Lord!” Sandanis responded immediately, as he gestured briefly towards a herald, who, having already heard and memorized the king’s message, immediately ran off to obey him. Sandanis was worried to see a hint of desperation had appeared in his king’s manner; his second encounter with these Persians had taken its toll on his nerves. Even so, thought Sandanis, his actions were sound; after the terrible defeat of his cavalry, there was nothing for it but to retreat within the city’s impregnable walls and sit out the siege until help could arrive.

“How long do you think we can hold out?” the king now demanded. “Your majesty,” Sandanis responded reassuringly, “we’ve plenty of supplies; enough to last several years. As long as we keep the walls well manned by guards and archers, we can hold out almost indefinitely…” Croesus looked only slightly relieved, although he seemed satisfied enough with his general’s response. Though he had been severely shaken by the ferocity of the Persians, he was most certainly not beaten yet! As soon as his allies arrived he was determined to have his revenge on these Persian barbarians.

*** ***** ***

The Lydian herald soon arrived in Laconia, the capital city of the Spartan state of Lacedaemonia, to find the Spartans grieving sorely for the loss of three hundred of their best warriors in a recent dispute with Argos over the territory of Thyrea, whose ownership they both claimed. Even so the Archon greeted him warmly, although he didn’t quite know what to make of this unexpected visit:

“This is indeed a surprise, herald!” The Archon said, “We had not thought to hear from you again until we go to meet your master in Sardis in spring…”

As he spoke, the Archon could not help noticing that the herald seemed to be having a hard time keeping tears from his eyes as he answered, “Alas my lord, the gods did not will it so; our city of Sardis is already besieged by Cyrus; my master bids you to honour our alliance and come at once!”

“And the siege?” the Archon demanded, needing to know more details of Croesus’ situation before he would commit his troops to an ocean voyage, especially at this stormy time of year, “Is Sardis likely to hold out long enough for us to relieve her?”

“Yes lord!” The herald replied stoutly, “Our walls are strong and high and the city is well-supplied…”

The Archon thought deeply for several moments before he spoke again, “We are at present engaged in a dispute with Argos over Thyrea; the mourning you see is for three hundred of our best warriors, who have died already in the dispute.” Now, the herald thought to himself, he finally understood the reason for all the weeping and lamentation which he had observed on his arrival, as he looked around at the huge crowd of mourners, who had now ceased their wailing while they waited to hear whatever news this Lydian had brought with him.

When he saw the extent of the Spartans’ grief however, he couldn’t help but wonder if the Lacedaemonians would even be able to help. He need not have worried on that score, however. The Spartans felt that a man was only as good as his word; if Lacedaemonia had made an agreement to help Lydia, then whatever the cost to her in either men or materials she would honour it; all the more so as Sparta was indebted to Croesus for many kindnesses.

When the Archon saw and understood the distressed look which had appeared on the Lydian’s face, he continued, “We are obliged to avenge their deaths, yet we will not dishonour our treaty with Croesus; tell your master that as much of our forces as can be spared will be assembled at once; we will sail for Sardis as soon as the ships can be provisioned.”

“Thank you, my lord Archon.” The herald replied gratefully, nodding his thanks. However, privately he could not help but wonder whether the Spartans would in fact be able to send enough men to turn the tide of this war against the Persians. Having just lost three hundred of their finest warriors in their dispute with the Argives over Tegea, they would, he thought, undoubtedly lose many more men avenging their deaths. Who, he asked himself, could possibly know how many troops Lacedaemonia would be able to send to Lydia after they had revenged themselves on the Argives?

Even so, the herald thought to himself with grim resignation, a little help is better than none. Negotiations now being at an end, he gave the Archon a farewell salute and said, “I shall return immediately and let Croesus know that help is on the way…”

*** ***** ***

Julian,

After a little thought and meditation, I’ve come up with the following hypothesis… (really just a guess…):

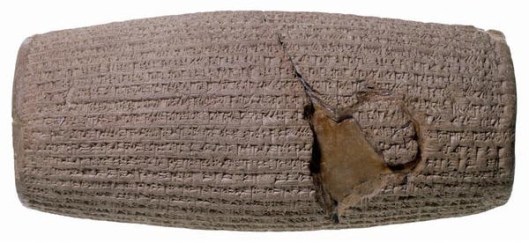

I’m no expert on cuneiform writing, but cannot help but wonder whether or not we are seeing this cylinder as it was meant to be seen… It seems more likely to me that it was meant to be viewed standing on end; the fact that the writing seems to go all round may be evidence of this…

And if this is so, it was most probably placed on a pedestal, raising it to a comfortable eye-level…

Was it found in Babylon? No matter… whichever city it was found in must have eventually been deserted and fallen into ruin… at some stage after this perhaps there was an earthquake in the region (Santorini?) which may have shaken it from its pedestal, and it must have fallen onto some other, probably metallic, tubular or cylindrical object which chipped out a neat two-thirds of a perfect oval as well as the other missing ‘wedge’…

Whaddaya rekkn’?

😉

LikeLike

Only just come to this story and your comment. Bloody renovation and Christmas shenanigans is taking all my time.

All I can see is a fucking great big tyre, blown out, probably from too much use on the machines and trucks pilfering all those minerals in the open wound mines.

LikeLike

As always, lovely words Asty.

There is a lot that anyone in a Croesus situation can be happy about.

Here a poem;

LikeLike

Thanks for the compliment, Gez… and your poem’s words are truly beautiful! Leonard Cohen at his very best.

🙂

LikeLike

Asty, I’m offended; camels are not ugly creatures, they can’t be, they are related to alpacas 🙂

LikeLike

My apologies, Helvi, but those were the opinions of Croesus’ horses, and not my own. Although camels are far from the prettiest of quadrupeds, ‘ugly’ is perhaps too strong a word for any beast so beautifully adapted to its environment.

Oftentimes one hears the old cliche about camels being a ‘horse designed by a committee’ as a critique of the committee system and/or process… to which the defense is that although they may not look pretty, these noble creatures are in every respect as useful, or even more useful than mere horses…

Once again I find Spike Milligan’s famous words appropriate:

“Beauty is in the eye of the beholder;

Get it out with Optrex!”

😉

LikeLike

Regarding the picture of the cuneiform tablet. That bit in the middle of the victory speech; was that the bit the scribe didn’t get? The bit obscured by wild cries of approbation and hysterical applause?

Or was it dropped after firing? Or worse. Some revisionist coming upon the tablet later, decided on a bit of editing so out came the chisel.

Vexed questions of archeological interpretation.

The great yarn continues.

LikeLike

…moderators lurking behind the olive trees, with chisels in their pockets!

LikeLike

Nyuk Nyuk Nyuk. V funny H.

LikeLike

…the Athenians sang…

LikeLike

And, of course, the Spartans never sent out large enough forces to win any battles. The population was just too small for that and their manner of governing very discouraging to population growth. Ruthless regime that preferred killing to nourishing -even its own population.

Certainly not nourishing the mind and what with their one-dish cousine of black soup, their bodies didn’t get too much help either.

It was a fascinating little state that one. Hard to picture it. Two Kings, each with two advisers (archons) on top of, not a society but an army. Flimsily built barracks, not houses, not building, certainly nothing of artistic merit, no schools, just barracks of men who spent their day, either “culling” their slaves (helots) or culling each other as military exercises and learning pithy little (laconic) slogans, like Μολὠν Λαβἐ (Molon Lave=Come and get it, if you dare) and ἠ ταν ἠ επἰ τας (said by the mother to her son, as she hand him his shield on his way to war=Either return holding it triumphantly or be brought upon it killed.) Plato called it “timocracy” Honour-o-cracy.

And as for their alliances! Honour played a slippery role there. The Athenians sand and dramatised their myths; these guys lived them.

But an exciting read asty, many thanks.

LikeLike

…the Athenians sang and dramatised…

LikeLike

Black soup? Was it made with blood and black beans?

LikeLike

Pig’s blood and vinegar, Helvi.. Not much of a recipe! I think my opinion of it would echo that of Pausanias: “Now I know why the Spartans are so eager to die in battle; they have nothing worth living for!” (Or words to that effect; apologies to professor atomou for any misquote!)

🙂

LikeLike

No, atomou; thank YOU! Praise from you is praise indeed!

🙂

LikeLike