Story and Pictures by Warrigal Mirriyuula

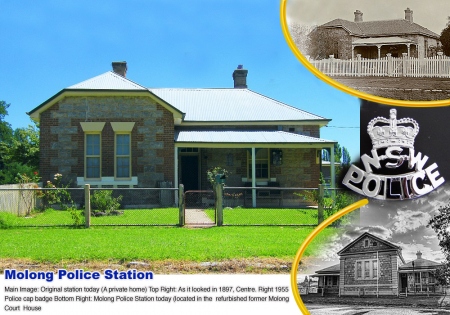

Sergeant Fowler rode his bicycle over the cattle grate in the entrance to the Police Station yard, coasted to the wall and dismounted. The morning sky was dark and overcast but he’d beaten the rain. Taking his wadded tunic off the rack, he pulled his bicycle clips from the serge legs of his uniform trousers and shook his legs to straighten the crease. Taking off his dry slicker then donning the tunic, doing up the shiny brass buttons and straightening his collar he said to himself, “Right, ready for action.” and walked through the rear door into the cell vestibule. Some drunk was snoring in the cell.

Young Molloy, the new probationary constable, was brewing up and waiting for him with the incident report from last night.

“Pretty quiet Sarge. There was a bit of a barney at The Freemasons just after closing. Nugget Henderson got the worst of it. Seems he slagged off that new barmaid and the other drinkers didn’t take it too kindly. He’s got a split lip and a black eye, but I think he’s gonna be all right. I cleaned him up a bit and put him in the cell to sleep it off. ‘e’s been snorin’ and fartin’ all night. His face is a fright but there’s nothin’ serious.”

“Hmphh,” said Fowler. “Nugget’s a bloody pain in the neck. Silly bastard gets all full’a’piss and bad manners and starts lookin’ for a fight. Any reason’ll do. Leave ‘im there ‘til he wakes up on his own. No point chargin’ the bastard, ‘e’ll just do it again nex’ time he gets pissed and the fancy takes ‘im. Better off lettin’ the pub punters give ‘im an adjustment ev’ry now and then.” Fowler turned and looked over young Molloy’s shoulder, “Char ready yet?”

“Jus’ brewin’ Sarge” said Molloy as he went to shovel generous helpings of sugar into the chipped enamel mugs.

Molloy looked down at the paper in his other hand. “We had a call early in the evening from the manager out at MacGuire’s place. Seems he reckons some of their prize rams have been interfered with. He wouldn’t say what he meant by interfered with. He just said, an’ I’m quotin’ Sarge, “Your ignorance on the subject of prize merino rams would be almost absolute, so there’s no point explaining myself to you. Just get Fowler out here in the morning toot sweet.” Molloy handed the report to Fowler. “Is he always that rude Sarge?” he asked with a look of frustration.

“’fraid so, Molloy. Fred Bagley’s a cast iron bastard. He’d sell his gran’mother for an extra pound of greasy superfine. Mind you, that place runs like a clock and old MacGuire’s got more blue ribbons than anybody else ‘round ‘ere. That flock’a his is worth a fortune so I better get out there and see what the dickens is going on.”

“Righto Sarge.” Said Molloy collecting up his kit. “I’m off home for some kip.” Molloy looked out through the front of the station. “I’d a thought that Chilla’d be in by now. Do ya need me to stay Sarge?”

“No son. You get off ‘ome and get yer ‘ead down. Chilla’ll get here sooner or later.” Fowler replied, distracted as he looked again at the incident report. “Hang on a mo’ Constable.” Molloy turned in the doorway, “Wha’s this about some old swaggie bein’ seen down by the silos?”

“Oh yeah. Prob’ly nothin’ but I put it in the report. Jack Tenant down at the railway station said he saw this swaggie collecting the spilled wheat from the around the base of the silos. Got most of a sugar bag full and then headed off down the creek. Just a stranger, but ya never know.” Molloy waited to see if Fowler had further questions.

“Yeah, prob’ly nothin’. Said Fowler. “You get off ‘ome…, unless ya want a cuppa?”

“No thanks Sarge. I’m beat, to tell the truth. Bed’ll do me just fine.” And with that he turned again and went out through the cell vestibule. A moment later the kickstarter on Molloy’s Matchless 350 Single could be heard as the young Constable kicked his ride into life. Soon enough the deep bass grumble of the big single could be heard as Molloy gave it some throttle. The boy obviously loved the cacophony of deep bass cut with sonic cracks as the exhaust valves opened. A moment later he heard the Matchless clubble over the cattle grate and then tear away off towards the guesthouse where Molloy had his digs.

“Temporary Australian”, thought Fowler as he sat down at his desk and got out his diary. He remembered all the dispatch riders during the war riding just these bikes. They’d all been mad keen for speed too.

“Righto”, said Fowler to himself, taking a sip of his tea and making a short entry in the diary, “Once Chilla gets in I’m off.” It looked like he’d be out most of the day. He’d have to go out to MacGuire’s. Bagley was a bastard, always looking for confrontation, but there might be some genuine situation. He’d also been trying to get back out to the sawmill for the last couple of days. There’d been a break in and he just wanted to follow up on a few questions with a couple of the blokes. There was a growing suspicion niggling at him that it was an inside job. They were hard men up at the mill and a few of them had priors for assault and theft. Thirty-Five Pounds plus shrapnel and a new chain saw might have been too much temptation for a bloke on minimum wage. “and I must drop into the Central School”, he audibly reminded himself again, as he had done all last week. He’d been asked by the headmaster to scold some kiddies who’d been throwing their lunch scraps over Mrs. Bell’s back fence. Apparently her cat had taken ill and she blamed the children’s scraps. He’d been putting it off but today he really would make the effort. It wasn’t exactly his jurisdiction but his appearance in uniform would keep the peace. Not an entirely redletter day for the law in Molong but then most days were like this.

Fowler heard Chilla’s little Morris van pull into the station yard just as the first rattle of rain on the roof started up.. He closed his diary and locked it in the top drawer of his desk, then checking that he’d left nothing sensitive where Chilla could get his sticky fingers on it, he went out to greet the painter. Chilla looked like he’d been dragged through a hedge backwards, and now he was getting all wet and bedraggled. He gingerly unloaded his paint and ladders, brushes and trays onto the verandah, pausing for a moment to rub his temples. He was here to redo the reception and interview room. The old station was showing some wear.

“You look completely knackered, Chilla mate, and the day hasn’t even begun.” Ribbed Fowler. “You need a good cuppa.”

“Big night last night Chook” said Chilla dumping an arm full of tarps and sighing as if already exhausted. “Went to a cricket do at The Canobolas in Orange. Pissed as lords we got. Singin’ blotto voce in the bus all the way home. I’d need ta shave a dozen dogs, I reckon.”

“Silly bugger,” said Fowler and returned inside while filling Chilla in over his shoulder.

“Nugget Henderson’s sleeping it off in the cell. He got a tune up at The Freemasons last night so he might sleep for a while yet. I’ve unlocked the cell. Just keep an ear out for ‘im and when he wakes up get him off the premises quick smart. No tea, no commiserations, the man’s a bloody menace to himself and everyone else.” He picked up his notebook and buttoned it in the top pocket of his tunic. “I’m gonna be out most of the day so you’ll be on your own. If I’m not back when you finish just lock up when ya go.

“Righto mate, no worries.” Said Chilla as the Sergeant disappeared through the cell vestibule to the garage out the back.

As the black Police ute pulled out over the grate Chilla went in to make himself a cuppa. It was now pelting down outside. In the cell Nugget let go an arse tearing fart, groaned and rolled over.

“Jesus Nugget, that smells like sup’m ‘as crawled up y’r arse and died.” But Nugget was still out to it.

As Chilla waited for the kettle to boil he began singing under his breath while leaning on the sink and swaying his bum from side to side, “Hi ho Kafoozalem, the harlot of Jerusalem, Prostitute of ill repute, Daughter of the Baba.” It had been a big bash at The Canobolas last night. The young NSW and Test all rounder, R. Benaud, had been the guest. There was talk he was captain material. The Molong team reckoned they’d hold off their opinion to see how he played at home against the Poms this summer. There was no doubt he was good, but just how good remained to be seen. Having made his tea he pulled the “Express” out of his pocket and went into the reception to sit and read the newspaper. There was a picture of Mongrel and The Runt on the front page.

“THE DOGCATCHER’S BEST FRIEND”

(Molong Express. Monday, Nov. 7, 1954)

“The new Ordinance Inspector for Molong, Mr. Algernon Hampton, got more than he bargained for when he took his utility for a drive along one of the Wellington Road ridgelines early on Saturday afternoon.

Though details as to his purpose there and what happened are still unclear it appears that two local stray dogs found Mr. Hampton’s unconscious body in Conway’s rye pasture. One of the dogs, a large mixed breed animal known affectionately to locals as “Mongrel”, then made his way to the Mitchell Roadhouse on the Wellington Rd. and raised the alarm.

Mr. William Martin, co-proprietor of the roadhouse, affected a rescue and the injured man was taken to the Molong District Hospital where he was attended by Dr. Albert Wardell of Molong. It is reported that Doctor Wardell was required to treat and stitch a serious head wound and that Hampton was suffering from shock and concussion.

The patient will remain in hospital until at least this afternoon, by which time he will have been seen by noted neurologist and head injury specialist Dr. Karl-Lenhard Gruber from Bloomfield Psychiatric Hospital at Orange.

Mr. Hampton has been lucky thrice in his injury. Firstly when his rescue was initiated by a dog that would normally be the subject of Mr. Hampton’s work obligations as local dogcatcher; secondly when it was Doctor Wardell who was called upon to treat his wounds; Dr. Wardell’s stitching and minor surgery skills are legend in the district; and thirdly by the availability of the renowned specialist Dr. Gruber to attend to his case.

I’m sure that all Molong will join with us here at the Express in wishing Mr. Hampton a speedy recovery.”

…and there was a picture of Mongrel and The Runt sitting on the hospital verandah looking straight at the camera. When had that been taken? The caption read, “Popular local canine identity “Mongrel” and his inseparable companion “The Runt” wait for news of the dogcatcher’s recovery.”

Mongrel looked proud and The Runt, as usual, was poking his head around from behind Mongrel. Those that knew him could almost have heard his little growl as he bared his yellowed fangs at the cameraman.

Up at the hospital Algernon stared at the photograph lost between incredulity and simple confusion. Those dogs again. His role in the affair seemed secondary, somehow uncertain; and there behind the dogs was the window, inside under which his bed was located. If he had popped his head up at the time he would have been in the picture too. He munched on his toast and marmalade, taking the occasional sip of tea. He brought the newspaper nearer to his good eye and peered closely at the picture as if hoping for some further insight to appear from between the lithographic dots. None did.

The swelling had eased considerably and his left eye had opened after a boracic bath, but his vision in that eye was still blurred and unstable. The nurse had said that this was to be expected after such a knock and said that “The Doctor” would look at it.

Outside it was raining steadily. Algernon read the article again as he finished his tea. It made much of everyone else involved, including the dogs, but left him unable to decipher his own role in the events of that afternoon. “Details as to his purpose there and what happened” where somewhat confused in Algernon’s mind too. Mongrel’s role was emphatically clear. He’d been the hero of the hour and was now the talk of the town; there weren’t enough exalting clichés to cover his role. For Algernon things were less clear. There was a low distant rumble of thunder and the rain intensified a little. Algernon looked out through the flyscreen at the water dripping off the guttering and began to wonder why he was here at all.

He saw his father’s face in his mind’s eye and realised he’d have to call his family. His mother would be wondering why he’d only answered one of her many letters in the months he’d been away from home. He recalled getting the keys to his new ute, a graduation gift promised when Algernon had started at Melbourne University and his father still had every expectation that his only son would come into the family business and eventually take it over. His choice had unsettled his father, made him seem less certain and in the time between his graduation and his departure for Molong Algernon and his father had become somewhat distant and ill at ease with each other. Neither the young man nor the older knew how to say what they wanted to say and so it remained unsaid.

On the morning he left he had received a stern departure speech from his father full of manly advice and life tips he barely understood. His father thought his choice of job incomprehensible. A young man with an honours degree in history didn’t become a minor functionary in a distant local government apparatus; and Algernon had been completely unable to adequately answer his father’s question as to just why he took the job in the first place. His mother had sweetly kissed him on the cheek and said with a tinge of sadness, “Be your own man; it’s you life now, make your own way.” She’d hugged him like he was going off to war. “We’ll always be here.” She snuffled and wiped a tear away. Her boy was going out into the wide world. She’d never even heard of Molong. He’d seen them in the rear view mirror as he drove away. His father, stiff, straight, still with that look of incomprehension, his mother gripping her husband’s arm, her head on his shoulder. Algernon couldn’t make out the tears but he knew they were there.

Algernon’s reverie was broken by Harry walking up the middle of the ward flapping the “Express” in front of him. “You’ve made the front page, “Scoop!” It seemed everyone was trying out a nickname for him. “Good picture of Mongrel don’t ya think?”

The dog did look good in the picture. Proud and handsome. Algernon perked up at Harry’s return. He’d grown fond of the old butcher in the few days they’d been ward mates. Harry didn’t give a toss. It was all the same to him and his devil may care attitude was infectious. Algernon’s headache had receded to a minor throbbing.

Harry sat on top of his bedclothes. They’d removed his catheter and he was now dressed in his own pyjamas. He was feeling much more himself.

“You’ve got that trick cyclist from Orange th’s’mornin’,” Harry said as he turned and folded the paper to look at the sports page. “Ya wanna be a bit careful about what ya say to those blokes. A lot of ‘em aren’t right in the head ‘emselves.” There was no malice in Harry’s pronouncement. He didn’t care if they were crazy on their own time. To him this was just friendly advice. Psychiatry was obviously mumbo jumbo and you had to be prepared. “He’s not a real doctor like Doc Wardell.”

Harry found whatever it was he was looking for and bringing the small pencil down from behind his ear he began to make notes in the margin of the paper.

The nurse came in with news that Doctors Wardell and Gruber would be here shortly. She set about straightening Algernon’s bedding then began removing the main dressing over his wound and cleaning the suture lines. She worked quietly and efficiently, occasionally looking into Algernon’s eyes and smiling at him, reassuring him in a way he found very comforting. She had a fragrance not unlike vanilla.

Monday was Beryl’s unofficial day off. After getting the guest breakfasts together and getting the kids off to school, the rest of the day was her own. Alice MacGillicuddie was also enjoying a rostered day off and had called to suggest she and Beryl get together. On Mondays Mrs. Delahunty did the lunches in the Telegraph dining room and there was always a number of bookings; seventeen today including Doc Wardell and that strange German doctor from Orange. Mrs. Delahunty would enjoy that. Doc really enjoyed good cooking and Mrs. Delahunty thrived on culinary flattery. Once Mrs. D arrived Beryl and Alice MacGillicuddie where going to do a little shopping at The Western Stores and then they’d return to the Telegraph to sit down for a good natter over a late morning tea and Boston Bun. They’d been friends since Jenny’s birth and treasured the time their busy lives allowed them to spend together. Though both women were active in the CWA it was their tea mornings and shopping expeditions they enjoyed most; when they could be alone, just two girlfriends on a lark. As Beryl sorted out a few minor matters in the kitchen she could hear Alice coming through the servery. “Beryl,” she called, “have you seen today’s paper?”

Across rain splattered, gutter bubbling Bank Street at Andrew’s Newsagency Old ‘drews was tidying the main counter while Young ‘drews brought another stack of The Express out from the storeroom. They’d been moving like hotcakes. The Express at a Penny didn’t usually sell as many as The Central Western Daily at Tuppence but today, with the heroic picture of Mongrel and The Runt on the cover, it was running out of the shop like an Olympic sprinter.

Woof woof, yo.

LikeLike

V stylised Hung. 🙂

LikeLike

Glad to be of service 🙂

LikeLike

“I’d a thought that Chilla’d be in by now.”

“Chilla’ll get here sooner or later.”

“Once Chilla gets in I’m off.”

To quote any more of these references would risk revealing too much … the nuts and bolts of the poetry of this chapter. That is delightful. Anyway, must go and get some sleep. 🙂

LikeLike

That’s right, ‘shoe, some authors spill their guts in the first line, leaving nothing to build up. Might as well chuck a pie in a blender. No, the ‘who’s who’ in Molong is slowly revealed, a bit like life.

Plus our canine heroes have reached cult status.

LikeLike