13 Mongrel and The Runt by Warrigal Mirriyuula

Chook went to see MacGuire as evening fell, but found him absent on a business trip to Sydney. He wouldn’t be back for a few days.

His wife mentioned that Bagley had told her of the loss of the prize Merino rams. Chook asked her to ask her husband to call the station as soon as possible. Mrs. MacGuire, ever the charming hostess, had offered Chook tea, but he’d declined, siting pressure of work and many a mile to travel before the night was through.

Mrs. MacGuire thought this a little cryptic, but she wished Chook the best of fortune with the investigation. He was leaving when he paused on the verandah steps. He turned, Mrs. Macguire was standing in the verandah light.

“What do you think of Bagley? Chook asked directly.

At first she seemed somewhat taken aback. “Well, I don’t know. I don’t really have much to do with the man. He’s my husband’s creature.” She pulled her cardigan tighter around her and twisted, just slightly, adding, “My husband does rely on him a good deal.”

She paused as if deciding whether to go further.

“Actually, the truth is I don’t like him much.” She pronounced with a pout. “In fact I don’t see much to like. He seems filled with anger and belligerence. I try to have as little as possible to do with the man. His wife is sweet though, in a heavily put upon sort of way.” Mrs. MacGuire paused again, then added in a low conspiratorial tone, “I don’t think she likes him much either.” Nodding to confirm the powerful truth of this last opinion.

“Mmmmm,” was all Chook said. He turned and left Mrs. MacGuire standing in the porch light watching him go. He was halfway to the gate before the light went out.

His next call was on Miss Hynde at The Pines. The visit was more out of curiousity than a need to cross all the “t”’s and dot all the “i”’s on the incident report. The old bird was often gossiped about in Molong but she was seldom seen. Indeed Chook had never laid eyes on her, but she was known around town as “that crazy artist lady”. She was known for having strong opinions and offering them at the drop of a hat. She argued with men, often besting them, and lived by herself in a world of dottery weirdness, painting pictures and sculpting objects more at home in a mental institute, or so the local legend went.

When Chook pulled up out side the picket fence surrounding the little white weatherboard cottage it was getting on for full dark. All the verandah lights were on, as were all the interior lights as far as Chook could tell.

The place was aglow again, just as it had been this afternoon when Chook had first laid eyes on it. The glow gave Chook a warm welcoming feeling. She couldn’t be that hard to get along with.

Then there she was, suddenly striding down the path, her long grey hair falling out as she pulled away a scarf. She shook her head and scratched through the tangled hair.

“Police ey?” she challenged, but Chook was just gobsmacked.

“What do you want with the mad woman of Molong Sergeant?” She was carrying a number of big brushes, wiping them with an oily cloth. “Come on man,” She slid the brushes in the hip pocket of the spattered bib and braces she was wearing, “spit it out!”

“Ah, Miss Hynde? I, ah, um,…” Chook just couldn’t get back to an even keel.

“My god man! We’ll all be murdered in our bed’s if you’re our protection.”

She smiled, amused by Chook’s discomforture.

“Yes I’m Miss Hynde, though why the yokels insist on the “Miss” is a continuing mystery to me,” She openly appraised Chook like a stud master might look over a stallion, “And you’re the local plod, so I imagine at some point you’ll be able to form a coherent question, hmm?”

Chook finally pulled himself together to ask, a little too formally, like a boy might play a policeman in a school play, “I need to talk to you about the fire you reported on MacGuire’s place.”

“Yes, I’d already worked that out Sergeant.” She gave him a smile that sent a shiver of dread and at the same time a thrill of excitement through him. He fervently hoped none of this was intelligible to her.

“Come on…” She grabbed Chook by the arm using both hands to hang onto his bicep. She pulled in close and dragged him up the path. There was an urgency and an intimacy in her grip that just added to Chook’s confusion. “What a funny fellow you are.” She said with a lilt in her voice as though she was encouraging a reluctant child to accept a fundamental change.

Chook silently allowed himself to be dragged into the chaos and confusion of the cottage. In his current state he fitted right in.

Miss Hynde wasn’t a mad old lady at all. In fact Chook wouldn’t have put her past about thirty, thirty five tops, and maybe that was just because of her thick, wild, salt and pepper grey hair, and her face had both such strength and beauty, her eyes penetrating, dark and knowing.

Chook was all at sea, from the moment he entered the house with her. Just when he thought he had himself under control she would smile at him, or ask a perspicacious question regarding some as yet unconsidered aspect of the fire, or she would just look at him, almost daring him to be himself in front of her. He thought. Perhaps.

She had no other helpful information about the fire other than that which was already contained in the report he’d had from the fireys, but it still didn’t occur to Chook that he might leave her, there in the glowing cottage in the pines.

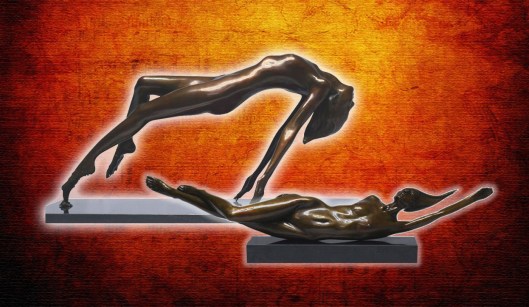

He realised he had been waiting for a kind of permission, like a note from a senior officer, something. She made him feel so not himself, there in her glowing house surrounded by things that just made Chook’s brain spin; confronting paintings of sides of beef, mixed with what looked like aboriginal designs; the dead meat oddly full of colour and life; plaster and bronze sculptures of tortured, animalistic things that none the less appeared full of potential, as though they might suddenly explode, shattering the cottage.

Then Chook saw two small lithe bronzes of a naked woman in impossible poses. He couldn’t take his eyes of them. It dawned on him that they were of her, Miss Hynde; younger, but the face was unmistakable.

“These..,” his hand flapped at the sculptures, “They’re of…., that’s to say, they’re… you….” Chook tried to say how much he appreciated the two sculptures but couldn’t work out a form of words that didn’t make him sound like a simpleton making some boorish observation about her nudity.

He knew nothing of art but Chook knew he liked the artist, he felt the power of her work slowly unmanning him. He smiled boyishly at her, and she laughed unselfconsciously back and grabbed him.

She has mistaken my confusion for intelligent interest he thought, as she dragged him, again, out the back to the converted shed she used as her foundry, there to reveal with a stagey flourish from beneath a stained dust cloth, a huge bronze statue of a man anchored at the hips to the stony ground, his burnished torso a twisted exposition of human anatomy in tension, the head thrown back, mouth at full gape as if screaming, the arms were upraised to the rough rafters of the shed, the fingers both pointing in righteous accusation and pleading in humility. Chook had thought it simply awesome; his mind was stunned; and she had imagined and realised all of this.

“I call it “Terra Nullius”.” She said matter of factly.

Did he actually black out? He thought not, but he couldn’t remember how exactly, but she must have walked him to the ute at some point. He didn’t really come back to earth until he found himself turning the key in the ignition. He rested his arm out the window, she softly placed both her hands on the bare skin of his forearm. Gripping him lightly and crinkling her nose, she said, “You’ll work it out,” she paused, kissed him softly through the open window, “You must come again.”

She had then smiled sweetly, an unexpected softness she had not shown before, that sent him tumbling again. She turned and walked briskly back into the house.

It was too much. Chook had never met a woman like her. In fact he would have denied that women might behave this way, until a few minutes ago that is. Now he couldn’t understand why all women didn’t think that way, behave that way, be that way; but it was still all too much.

Chook shook is head, his face still immobile as his mind raced on the subject of Miss Hynde.

He hadn’t got her Christian name.

“Shit Chook, pull yourself together!” he said aloud to himself as he put the ute into gear and set off to see Bagley. He probably should have gone earlier, but Bagley was such a pain that Chook had simply put it off, and now he wondered if he was in any fit state to hold up against the fusillade of withering abuse that was Bagley’s usual style.

Miss Hynde had rattled him he realised, but his policeman’s pride, indeed his manly pride, would not allow that he’d had his heart bushwacked, his mind turned over like a Spring sod, and the deed and title to all that was Chook was already on its way to its new owner.

“That way madness lies.” Chook found himself unexpectedly remembering his schoolboy Lear, “No more of that.”

Old Jack Enderby would be proud after all these years. But then it occurred to Chook that the quote mightn’t be “ap-po-site”. He chuckled happily. That was another of old Enderby’s words, kept for special occasions; occasions that were “ap-po-site”, Chook chuckled.

As Chook turned off the main drive to the MacGuire homestead, Bagley’s cottage ahead, caught in the swinging headlamps, he steeled himself for what he imagined would come; but Chook wouldn’t let the bastard get the better of him tonight. In fact, disregarding the maddening siren song of Miss Hynde, Chook was feeling pretty good. He was filled with a light-hearted confidence he realised. He felt younger, that was it. He was fit for it. He just wouldn’t let Bagley get up his nose.

The house was in darkness. One of the dogs chained up at the side set off barking as Chook got out of the ute and walked up onto the verandah. The house was silent.

Chook knocked heavily. At first there was no reply, then he heard movement. A light went on inside, then the verandah light. Chook heard Bagley say from inside, “So ya back, I knew you….,” then the door opened and Bagley saw it was Chook.

Bagley didn’t finish. He seemed disappointed and just said, “Oh its you Fowler. Well you better come in; and wipe ya bloody boots man.” Bagley was ever the most reluctant host

Chook didn’t discover what it was that Bagley thought he knew, or who he thought had come back; but it was obvious Bagley was in a foul mood.

From there the encounter had gone as expected. Chook’s upbeat manner had harried and harassed Bagley’s abusive assault until Bagley had simply been sullenly silenced. Not that Bagley had provided any information of any substance. He seemed, just as earlier, only concerned with the sheep and their value, and the insurance report. He seemed very concerned with the insurance report.

Except to deny any knowledge of the body, he didn’t mention it at all throughout the interview, which was conducted by Bagley with a terse uncooperative economy that Chook at last interpreted as founded in an almost complete distraction. Bagley’s mind was somewhere else entirely. He gave the impression that if Chook simply disappeared in front of him, it wouldn’t have happened soon enough.

“Is Mrs. Bagley home? I’d like to speak to her too please.”

“Well you can’t. She’s not here.” Bagley paused to lick his lips nervously. “She’s gone to her sister’s to stay for a few days.”

It was obvious to Chook that this fragment of information was a lie and it had cost Bagley dearly to utter it. He was now openly enraged, barely able to contain his anger.

Chook had all he needed and it seemed all he was going to get at this time. He warned Bagley again about not going near the ruin. It was still a crime scene until Chook said otherwise. Bagley issued the same belligerent statement in response; that he would do whatever, go where ever was necessary, but Chook had stopped listening. He just turned and walked out on the still blustering Bagley.

Chook drove home and poured himself a whiskey before sinking in his favourite chair. He was weary but still felt all abuzz after the evening’s events, and now that his time was his own again, his mind slowing a little, he found that pleasant buzz tuning back to Miss Hynde and her paintings and sculptures, and her knowing, and her hands on his arm…..

She was on his mind again as Chook jounced the Police ute over the cattle grate into the station yard next morning.

He’d stayed long enough out at the scene to see the body removed and to ensure that all the evidence he and Inspector Beauzeville thought pertinent was recorded, photographed and put into the coroner’s vehicle for transport to Orange.

Young Molloy had had a long sleepless night and was glad to be shot of guarding the dead body.

“It’s bloody creapy,” he’d told Chook, “several times I thought I’d heard something, but it never turned out to be anything. Well I don’t think it was anything.” He added with a tone of qualification that showed the depth of his uncertainty.

Chook had noted the uncertainty, then sent him home, but the lad had stayed to the bitter end, claiming it was good experience for him. Chook thought it more likely he was just curious. It was the young probationer’s first dead body. He was a bright lad and Chook thought he’d go far in the force.

It’d been Molloy’s suggestion that somehow the sheep and the body were more connected than just being in the same fire, and that the carcasses shouldn’t be burned, but rather, kept on ice as part of the evidence haul. They were after all, supposed to be blue ribbon beasts, all four of them each worth more than a car.

They didn’t look like much now, but Molloy’s contention seemed to ring true to Chook. Beauzeville had agreed, bringing a satisfied smile to young Molloy’s face, and the remains of the sheep had been carefully separated, individually bagged and put on ice.

Back at the station Chook called the veterinary pathologist at The Department of Agriculture in Orange, letting him know that the four carcasses were on their way to him for examination and analysis. He ordered the full array of tests and asked the pathologist if there was any way that he could prove the dead sheep were the animals Bagley claimed were missing from MacGuire’s flock. The pathologist offered his best efforts but couldn’t guarantee an outcome.

Hanging up the phone and settling down with his cuppa, Chook pushed his chair back and put his still muddy boots up on the desk, taking a long slow slurp on his tea.

It was time for a little more reflection.

—oo000oo—

When Algy awoke in the unfamiliar surroundings of the bedroom in Shields Lane he found himself confused and it took a moment for him to get oriented as to where he was and what he was doing there. His little Europa travelling clock showed 10:15. Algy hadn’t slept this late in a long while.

He vaguely remembered Porky helping him up off the couch after last night’s long talk. He’d gone to sleep with a spinning headache, which had woken him again in the small hours. He’d scrabbled around in the dark for a couple of the pills Doctor Wardell had given him and after that it was just oblivion.

There was a cold mug of tea on the bedside table, and a note:

“Make yourself at home. If you need anything Porky and me are at the shop.”

Algy pulled himself out of bed and sat on the edge of the mattress. He’d slept in his underwear. In the last few months he’d often slept in his clothes, but never in his underwear. His mother would “tut”, but Algy found a new kind of freedom in the notion of going to bed in his underwear. Maybe in summer he wouldn’t wear anything at all.

He casually pulled on a pair of pants and a shirt. He didn’t bother to button up, and as he made his way to the toilet his shirt flapped in the spring breeze blowing through the house.

While taking a pee Algy looked out the small open toilet window and was struck by the ordered regularity of Harry’s vegetable patch; the stakes and strings in straight rows, the hose wound onto a rusty old spoked wheel. Harry was a real “doer” alright, and Algy, from his vantage point over the loo, could now confirm Porky’s Fairbridge aphorism from last night. The grass always grows greener over the septic tank.

Flushing and buttoning up his fly, Algy had a chuckle to himself while he washed his hands.

He went into the kitchen to make a cuppa.

Gripping the enamel mug with both hands, Algy took a long pull on the hot sweet tea and sauntered barefoot down the hall, enjoying the warm morning air blowing gently through the screen door. Pushing it open with his foot, he went outside onto the verandah and sat in the morning sun to finish his tea. The dogs’ bed was abandoned.

Shields Lane was quiet. There was not a soul in sight. A dog barked round the corner on Riddell Street, Magpies were warbling along the side of the house as they hunted in the grass, and far to the east, up high, a Wedgetail was lazily riding a thermal.

The town seemed shrouded in an expectant hush, until, from the direction of Bank Street, Algy heard a bloke shouting instructions to a mate, but he couldn’t make out what about.

He went down to the gate to have a sticky beak.

Resting his mug on the flat top of the gatepost finial, he took a look up and down; there was no one in Shields Lane, it was still deserted; but Algy noticed, framed in the end of the lane to the north, the Town Hall on Bank Street.

At first it seemed like a mild admonishment, the building reminding him of his failure as a dogcatcher. That soon passed as Algy realised that while he had no clear idea about his future, the Town Hall and the responsibilities of the Ordinance Inspector were already rapidly receding into his past. He smiled again at his foolishness and shook his head. It throbbed once or twice to drive the realisation home.

He picked up his tea and went back inside. He’d decided to write a letter to his parents. They’d be worried by his infrequent communication and he had some thinking to do that he always found best pursued in writing rather than on the phone.

Dear Mum and Dad,

I’m sorry I’ve been so tardy in my letters to you both. A few weeks ago I might have said the reason was that I was too busy, too much to do, but the truth is that in a curious way I lost myself shortly after coming here. You were right Dad. It was a decision I didn’t think through. Later today I’m going up to the Town Hall to hand in my resignation.

It was an odd thing as it’s turned out. It’s changed me. Almost as if it was predestined, as though before I was just a character following the text in a rather obvious novel.

Having “run away from home”, when I got to Molong it was as if I placed myself outside the local community, by choice, and then suffered the consequences of that deliberate and unthinking choice. It wasn’t that people were uncaring or unkind. Indeed I’ve discovered in just the last few days that this little village is filled with people of an uncommon compassion and wisdom; a wisdom more profound than any I managed to glean from my studies.

But I’m already getting ahead of myself and I want to tell you both everything. So I’ll start at the beginning and try to include all the salient points.”

“But how to say it.” he pondered aloud. “What are the really salient points?”

Algy stopped, his pen poised above the paper. How could he describe the change when he was uncertain just how far that change had gone?

Just then the spring hinges on the screen door skirled and the next thing, Mongrel came bounding into the living room with Porky and The Runt close behind.

“How are ya mate? Feelin’ any better?” Porky had obviously been sent home to check on the patient.

“Better than I’ve a right to feel. In fact Porky,” Algy tried out his new friend’s name for the first time, “I feel like a new man, as if the world is my oyster.”

“Yeah, w’ll hang on a mo’. I got some steak here f’ ya lunch. Ya gonna need ya strength to open that oyster.” Porky responded as he walked through into the kitchen, amusedly muttering, ”Cracked melon, and the world’s ‘is bloody oyster, ark at ‘im.”

Mongrel had his paws up on Algy’s leg, his great red tongue lolling out panting, his bright eyes looking for any indication from Algy.

“How are you my new friend?” Algy said quietly to the dog. He took Mongrel by the ruff of blue round his neck, giving the dog a scratch and shake. Mongrel was in heaven.

“Did you know that in some societies, if you save a person’s life you become responsible for that person.” Algy looked as earnestly as he could into Mongrel’s eyes. “Are you ready for that responsibility?”

Mongrel barked a happy bark and licked Algy’s forearm. He got down and walked off into the kitchen. Algy followed him.

Porky was already trimming a couple of big chunks of steak and tossing the off cuts to The Runt at his feet, the little dog’s darting eyes never leaving the meat in Porky’s hands. As each tid bit was flipped into the air the little dog jumped and unerringly caught the scrap, then gulped it down. Mongrel showed no interest in the scraps. As usual he stood back from the relationship between The Runt and the man. Besides Mongrel had a man of his own now.

“Is there anything I can help with?” Algy asked, feeling a little like an invalid. “I could make us a salad.”

“Salad…,” Porky shook his head with a big smile on his face. “Y’re a corker Head Case, you really are.” Porky was chuckling to himself again, then, “Nah, don’ worry bout it. I’ll cook us some chips and cut a tomata or two. Salad…” he chuckled and shook his head again. “Ya gotta keep ya strength up.”

Algy sat down by the sideboard and Mongrel lay down beside him. Apparently blokes in Molong don’t eat salad, Algy thought, looking down at Mongrel, who lifted his head and turned it to one side, uncertain as to what Algy meant by the slightly abashed look on his face. Perhaps it was nothing. Mongrel lay his head down again, giving Algy one last look. Algy winked at the dog. Mongrel blinked back.

Porky placed the hunks of trimmed steak on the griddle and they immediately began to sizzle furiously. He went to the icebox and got out some pre-cut potato chips, then a bottle of yellowish oil from a cupboard.

“Nick Cassimatty put me onta this one. Ya don’t fry ya chips in dripping. Ya do ‘em in this.” He held the oil out for Algy to inspect and just as quickly took it back and began to pour a goodly quantity into a shallow pan. “It’s olive oil mate. Makes the best chips, you wait.”

“I can’t wait.” Algy said with a small smirk. “These chips aren’t made from your special potatoes are they? You’d have to agree, you’ve shown an uncommon solicitude towards that sack of spuds. You’re always going out walking together Harry tells me. Apparently it’s quite a sight to see.”

“I’m in training.” Porky said shortly, obviously not wanting to pursue the matter.

“What, to become a King Edward?” Algy gibed with a smile

Porky gave him a quick glance, just to make sure he got the gist of that one.

“Yeah, well you wait,” he said in good humour, “You’ll love these chips. Won’ ‘e Butch?” The little dog was hardly ever out of Porky’s thoughts whenever they were together and it had become his practise to include The Runt in any conversation.

Porky, after tossing a couple of handfuls of chips into the hot olive oil, finished with a flourishing flip of the last scrap of meat to The Runt.

Porky leaned against the kitchen sink and folded his wiry arms, looking straight at Algy. Mongrel lifted his head.

“Billy Martin dropped into the shop th’ smornin’. He reckons you’ve rooted that ute of yours. Apparently y’ve buggered the sump and done some serious damage t’ the suspension.” Porky’s face attained a certain sympathetic sorrowfulness before cracking back to a smile. “Anyway, no worries ‘e says. He can get the parts in an’ fix it up for ya. Take about a week, maybe ten days, he says.”

Algy just nodded, wondering why all these people, strangers really, cared so much about him. He felt a flush of embarrassment come across his face and his eye’s pricked a little. Mongrel was instantly alert to Algy’s mood change.

“Are ya alright mate?” Porky suddenly asked, moving quickly towards Algy. Mongrel was up, alert, his tail stiff.

“No. No, I’m fine, really, I’m fine. I just…” Algy trailed off, uncertain of what he was “just”….. Mongrel nudged Algy’s hand and gave it a lick before slowly settling again.

“Ya sure?” Porky sounded unconvinced and quickly checked the dressing on Algy’s injury as if he might have been able to decipher the problem in the pattern of folds in the bandage. Everything looked all right.

“Y’ ‘ad me worried there for a mo. Ya came over all queer. I thought ya might be ‘bout t’ have a turn there.” Porky shook his head and went back to the stove. “Can’t ‘ave ya fallin’ over on the road to recovery, mate. Harry wouldn’ stand for it.”

Porky attended to the cooking as Algy gave Mongrel’s back a stroke. The Runt, watching Porky cook, occasionally turned to continue his ongoing assessment of this newest member of the pack. Porky seemed to like the man now. Maybe the man was alright. The Runt would wait and see.

I like the sculpture in the picture, very fluid lines…who is the artist?

I always found olive oil too heavy for chips, prefer light vegetable oil for that….

LikeLike

Just of to The PO, to collect my surprise FD pressie, or card. I’ll be happy with a nice card, although as littlest (6ft) son, has gone to the trouble of sending something express post…who knows??

On the olive oil: just a point of order here. The burning ponit of olivr oil is too low to use for chips or deep frying, which is why some rendered fatys are used, or vegetable oils. I use rice bran oile or peanut oil for high teperatures–but of course vegetable is fine for chips.

The Indians use Gee, or Ghee, which is basically clarified butter. Once the impurities in butter have been removed it will stand higher temperatures.

Always pleased to be of service ⅎ….. :)….♥

LikeLike

I think I’ll take a trip up to Hardley Normal and get a new keyboard. I’ve only got to breathe on a letter and it just pops into the word.

LikeLike

VL, just back from Bing Lee, Gez needed a new printer, nothing wrong with the old Canon, it just needed a new cartridge , the bloody thing cost $139.-, so we thought Samsung printer for $60.- was a better deal, especially as we don’t use it all that much 🙂 Also the Canon did not want to ‘marry’ his new computer.

LikeLike

PS. the letter ‘a’ in my latest computer will only pop up if I hit it with hammer. Sometimes I have to add all ‘a’s afterwords…

LikeLike

I can’t find those images again H, so I can’t say who they’re by. I just swiped them from the net. I couldn’t believe my luck when I found them. They were just what I’d written. They’re wonderful though. They’d be just the sort of thing that would catch my eye. Indeed they did.

All your points about which oil makes the best chips have been noted, however it is well established that Sche cooks the best chips in the world, attested to by no lesser authority that young Wordsworth who is a connoisseur of his Nanna’s chips. Sche uses olive oil exclusively. That having been said, our house fire started with a stove top chip fire, so perhaps there is something to what you say regarding the ignition point of olive oil, JL.

LikeLike

http://www.alibaba.com/product-gs/300440636/modern_bronze_statue.html

Found it for you H. The artists is Chinese.

LikeLike

Thanks for that Warrigal, the work is very beautiful. We had an Australian/English artist and his Chinese girlfriend staying in our cottage on the farm. According to them the art scene in Shanghai is quite amazing; they were both preparing for their exhibitions.

They used to come over to our house for a chat and for Gerard’s bread (made in the breadmaker), maybe the bread isn’t as good over there in Shanghai as their art 🙂

LikeLike

Lovely work. More characters, more going on, but, the story always comes back to the dogs, plus, a hint of romance!

LikeLike

Strictly speaking its all “romance”, being a novel not in latin and centred on the themes of the human heart. And I couldn’t let Chook down; he’s such an unassuming character, uncharacteristically satisfied with his policeman’s lot. He needs something to bring him out into the open and I think Miss Hynde might be just the woman to do it.

And can there be anything more romantic than the love of a dog, or for that matter the love of a person for their companion? Humans love in a tangled and occasionally uncertain way, but with dogs its all or nothing, sure from the first sniff, the first lick.

LikeLike

Great story Warrigal… wonderful characters… Can’t wait to hear the rest of it.

And I must say it’s good to see you’re feeling up to writing again… we’ve missed you!

🙂

LikeLike

It really is my pleasure Asty. These bits were written before I got sick. I’ve just tidied them up for posting. I’ve been sketching out the arc for this and two other long form pieces but I haven’t actually written all that much for some time. Other fish to fry.

I’m feeling quite well though. I’ve lost a little muscle tone and don’t have the energy levels I used to, but I’m assured that will come back with a little regular exercise.

At the moment I’m sketching out a cricket match for the next episode. HOO will be pleased.

LikeLike

By a strange coincidence, Warrigal, I too have not only lost ‘a little’ muscle tone and my energy levels are way down too… but I’m also ‘sketching’ a cricketing scene, if not an actual ‘match’ for the next episode of HH… which I felt moved to start writing after I read this piece from your good self… (it was mostly guilt which ‘moved’ me, I must confess! Thinking if you can do it while you’re still actually sick, I oughta pull my bloody finger out!)

Hopefully I’ll have finished the next episode by this weekend… at some stage or other… Wonder if I can include a scene which includes a woman with ‘auto-erotic’ gloves… Loreen hasn’t been doing much of late…

😉

LikeLike

Nice story Warrigal, now don’t forget the woman with the auto erotic gloves

LikeLike

que?

Auto erotica…like seeing to yourself while wearing driving gloves? That sort of thing?

I don’t remember that bit, but I’ll take your word for it, you evil little boy!

LikeLike

I wonder where the shows were held? I bet Bathurst would have been a big show. With alpacas one was not supposed to trim and shape them but many did, spent hours preparing, grooming and stroking the animals. The burrs in the fleece was at times a horrible thing to get rid off., it used to pull the fleece and an expert could tell from the fleece which part of a region the animal came from. Animal shows are something you take to and for many never get out off. It has a life of its own.

I always enjoy reading your stories Waz. You still carry your heart on your sleeve when it comes to those earlier years at Molong. It shows in the narrative.

.

LikeLike

Molong had its own show and still does, including alpacas, (http://www.onlysydney.com.au/sydney-nsw.php?id=23196) as does Orange and Bathurst. In fact just about anywhere that has a showground has a show. The shows started out as a way to get ideas and techniques flowing between farms and between districts. They are also a kind of mini field day, showcasing new machinery and agricultural products. I’ll be attending the Molong Show in a few weeks, doctors permitting. The CWA do a fantastic morning and afternoon tea.

They’ve also been a celebration of all that is country life and if you look through the link above they still are. (The ute competition is always fierce, as are the dog trials.)

As for my fondness for Molong, remember this is a piece of fiction. Molong never was really like this, but this is the way I feel about Molong back then.

As Hartley said.; “The past is a foreign country. They do things differently there.”

LikeLike

The CWA do many a wonderful thing. Mrs A, having grown up in the country (Margaret River) when we got married, was given a book by the CWA. “The CWA Cookery Book and Household Hints” first published in 1936. All the women were given this book when they married there. Hers is the Golden Anniversary Edition. There are many great things like Catering for 50 people, afternoon tea at fete, Wedding breakfast for 100 people as well as catering for a Public stock auction all great stuff. In this book they had a thing about tongues seemed to be the meat of choice.

The good thing about this book though is the simple cooking recipes. So simple anyone could follow them and we have. She still has rthe book and its well used,

The end has “hints that help in the home and preserve the temper” as well as “Laundry hints, soaps and pastes.

The interesting thing is there is a CWA near where we live and its still opperating, yet wel live 14 kms from the city.

LikeLike

We only showed alpacas a couple of times. The wearing of the white doctor’s coat and the strictness of ‘show rules’ was taking over from the fun and bonhomie. It was fiercely competitive. I just loved haltering the young alpaca and getting them to follow the lead without pulling the animal around.

This I achieved by a mixture of becoming a bit like an alpaca and gaining their trust. Towards the end I managed to do it withing 15 minutes that would take others days and sometimes ended with both owner and the alpaca rolling over the ground.

Alpacas are intelligent animals but also rather shy and generally don’t take to becoming a pet.

I always thought a good part of any show was the barbequed sausage with onions on a roll.

As for Molong not really being like the story, well neither was Fremantle in 1956, the Willy Willy at Woy-Woy or Scheyville, but they will never let me go.

LikeLike

Two of the missing flock were Napoleon and Squealer?

LikeLike

They were pigs JL, roughly the equivalent of say, Abbott and Bolt

The dead Merinos are ribbon winning Saxon Peppin cross stud rams. They’d have had names like Blue Magic, or Spellbinder. Names of Roman generals were also popular back then. I knew a ram called Flavius, and another called Orator because he was always bleating on about something.

In high school a mate of mine kept a sheep in his back yard to keep the grass down. He was called Harold, the sheep that is, and he behaved more like a dog than a sheep, including running to the gate when Keith and I approached. Keith lived with his nanna and she would spin Harold’s wool to knit Keith jumpers.

(Actually the dead animals aren’t prize winners, but we don’t know that yet. Chook, Karl and Algy have yet to reach that point in the narrative.)

LikeLike

He’ll await.

LikeLike

Well, they were pigs and then they weren’t. Remember? The card game. the dialogue. Two legs better!

Bagley sounds like the Major. A likeable fellow ☻☼ Misunderstood and lost in a sea of creeeepyness.

You are telling stories better now Warrigal. I know that my opinion doesn’t count for a lot, however your shorter sentences and clearer unambivalent dialogue is much more pleasurable to read, to an old Pommmie reprobate, such as my very goodself ☻☼☻☼

LikeLike

Yes, the tighter format, better punctuation and paragraphing, are all products of having simply written more words. The more you write the more the writing improves.

I enjoy it enormously and I’m glad you still do too.

LikeLike

Is this a repeat, or did we miss the number 13 of Mongrel and the Runt in the first place. Pleased to see them back whatever the case.

LikeLike

No it isn’t a repeat. Its entirely new.

I’ve had to reorder the numbering because of changes in the narrative arc. This episode comes after the discovery of the body but is notionally at least, before the action taken by the dogs over the sheep kill

LikeLike

Finished the story after family went back to Sydney .Molong is starting to look like a long lost Paradise, even a feisty artist woman has been discovered to enhance the tale : )

LikeLike