CYRUS

by

Theseustoo

CHAPTER 17:

The Assyrian Empire

An Importunate Deity

The progress of Cyrus’ expedition towards Babylon was slowed considerably when they came to the River Gyndes, a broad and deep river with a very strong current; which would clearly require either boats or a bridge to cross, for it could clearly not be forded. As Cyrus’ army drew gradually to a halt beside the riverbanks a sudden commotion arose from the van. One of the six sacred white stallions which pulled Cyrus’ great chariot, as soon as it had been released from its harness, had refused the restraining commands of its groom and had suddenly plunged into the river and attempted to swim across on its own. The current, however, was far too strong and the beautiful snow-white beast was quickly swept away downstream and drowned.

Thankfully, Cyrus had not been in the chariot at the time; he had been scouting the banks with Pactyas for fordable places; although as it turned out they had done so in vain. Distressed at the loss of one of his sacred charges, the groom immediately sought his master to inform him of the loss. He found Cyrus just as he and Pactyas returned from their search.

“My king,” the groom said with a deep bow, “I have terrible news to report…” Nervously he looked up at Cyrus, who merely stared at him silently, the intensity of his gaze now silently demanding further information. Even more nervously the groom continued, “As you can see, Lord, this river, the Gyndes, is both too wide and too deep to be crossed without boats, nevertheless, one of your sacred white horses tried to cross it on it’s own as soon as it was un-hitched from your chariot…” here the groom broke off to wipe away a tear which had sprung unbidden from the corner of his eyes, for he had loved his charges very dearly, “Such a courageous creature! But it did not succeed, Lord; it was swept away downstream and drowned. The god of the river has claimed it as a sacrifice!”

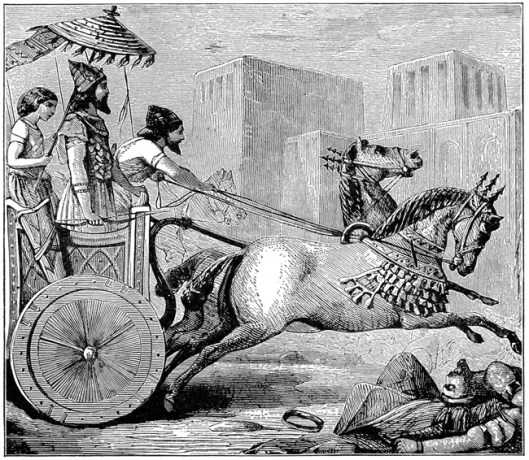

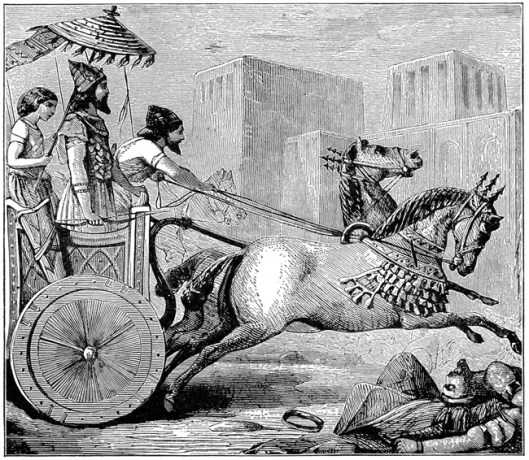

Cyrus' Chariot

Had it been any other horse, it would probably have been simply regarded as one of the inevitable losses any large armed force was bound to suffer on a major expedition; but as it was one of Cyrus’ own pure-white sacred horses, he took it as a personal insult. Another man might well think twice before complaining about such a sacrifice claimed by the river-god, but Cyrus was no ordinary man. His advisors had constantly insisted that his was no ordinary birth; it was foreshadowed with omens and portents they had said; the Magister had even said he had found Cyrus’ name in an old and obscure Hebrew prophesy which had suggested that he might well be the ‘Anointed One’; the Messiah whom the prophecy said would seize Babylon and destroy the Assyrian empire forever; and in doing so, unify the whole world. The manner of his accession to the throne, the Magister insisted, itself proved that it was certainly his destiny to rise from total obscurity to supreme power.

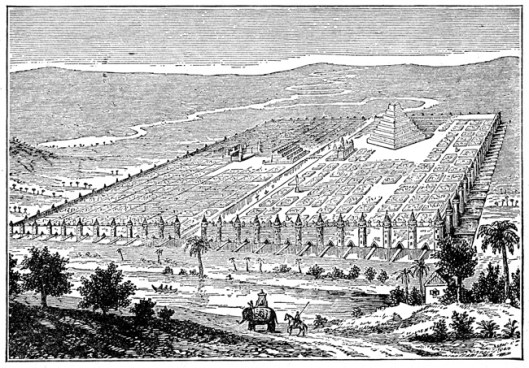

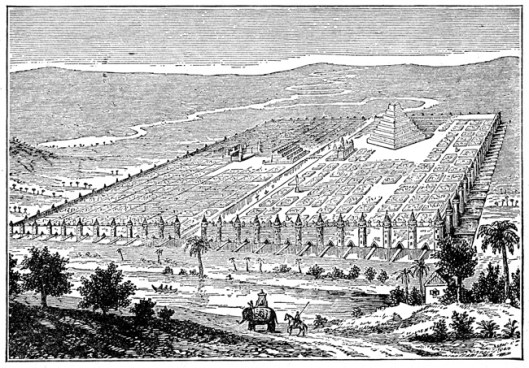

Babylon

At first Cyrus had wisely shrugged off such suggestions as fanciful, but as his empire had expanded, and victory piled upon victories were laid at his feet; often accomplished with remarkable ease, even in what were otherwise extremely difficult situations; that finally even Cyrus was persuaded that there may, after all, be some supernatural being guiding or even orchestrating his successes. The manner in which the path had been found which had given his soldiers the access they needed to Sardis and which had enabled them to take the city with little resistance, for example, had seemed even at the time like a gift from the gods.

The most ancient of all traditions held that a warrior who was victorious over all of his enemies; who thus subjugated them all to his own will, could only be the earthly incarnation of the son of the highest gods, Ea and Enlil themselves. Such a noble, indomitable and all-conquering warrior would eventually came to be recognized as the earthly incarnation of Merodach, their divine son; the Son of Heaven. Heracles, Cyrus had believed, was the last incarnation of such a demi-god, and before him, Perseus. But that he had been referred to as such even by his defeated enemies, he felt, was the final confirmation he had been waiting for before he allowed himself to be persuaded to believe in his own divinity.

So by the time Cyrus had reached the Gyndes, it was no longer any mere mortal whom the river-god had thus insulted with this involuntary sacrifice, but the Son of Heaven; a living demi-god, whose own status as the son of the highest god and goddess gave him superiority over any mere river-god. The insult to his dignity was thus, Cyrus decided, too much to bear.

“By all the gods!” he declared, “I cannot tolerate this insolence! The god of this river has overstepped his proper bounds with this theft! Have I not been called the Son of Heaven even by my defeated enemies? The god of this river must be punished! I shall break his strength so that in future even women will be able to cross it easily without wetting their knees. Divide the army into two parts, half on one side of the river, half on the other; I shall mark out trenches on either side of the river for the army to dig.”

*** ***** ***

Digging the channels which had been marked out by Cyrus cost him the whole summer and most of autumn; and now the first frosts of early winter gave the fresh morning air a crispy bite. Even so it was with evident satisfaction that Cyrus now surveyed his army’s handiwork, as he inspected the river’s depth with Hystaspes.

True to his word, the pair was able to wade across the river easily; the water coming only midway up their calves; and the current was considerably slowed; their knees were not even wet, Hystaspes noticed, as they climbed up the other bank, the gradient of which had been adjusted on both sides to facilitate the army’s crossing.

“Well then Hystaspes,” Cyrus crowed enthusiastically “we have shown this river, Gyndes, who its master is!”

Hystaspes, however, though pleased at his king’s success nonetheless felt that it had been something of a distraction from the main purpose of the expedition; and one which had cost them much valuable time.

“Yes my Lord;” he replied, a little wearily, “but we’ve lost the whole of the summer season digging the three hundred and sixty channels it took to do it!”

“Yes…” Cyrus drawled, thoughtfully. He could understand Hystaspes’ frustration; his general was eager to get at the enemy; like a hunting-dog, straining at the leash in its keen-ness to chase its prey, he thought. What Hystaspes doesn’t yet understand, Cyrus realized, is that by demonstrating my control over the natural elements like this, I have also just successfully completed my first act as a god. But somehow he felt that for him to say anything of this would still, he felt, have been rather immodest, so instead he simply ignored the implied criticism and changed the subject, “It looks like we shall have to winter here; we can raid the country-side for our supplies through the winter… we’ll attack in spring.”

“Yes your majesty,” Hystaspes said obediently, then, just a little hesitantly, he added, “but the disruption this will cause to the Assyrians’ economy will warn them of our intent to take Babylon.”

For such a great general, Cyrus thought to himself, the prince of the Paretacenae could certainly be obtuse at times. He found himself missing the quick, agile and subtle mind of Harpagus. Harpagus, he thought, would have been most amused by Hystaspes’ obtuseness. Patiently, Cyrus turned towards him, looking Hystaspes right in the eyes, so that he could see the twinkle that sparkled in his own, as the king laughed and said, ”Hystaspes, they know that much already! Their king, Labynetus, will be waiting for us even now, I’m sure.”

Hystaspes frowned; he was a little relieved that at least Cyrus was aware that his attack on Babylon would be no surprise to her current Assyrian occupants. Yet he was a little taken aback by what, to him, looked like Cyrus’ carefree attitude to their expedition. After all, he thought to himself, until Cyrus’ own great-grandfather, Cyaxares had evicted them from their capital city of Nineveh, thus forcing them to retreat to Babylon, the Assyrians had for centuries been the most powerful state in the world; Hystaspes could not help but feel that they were about to grab a tiger by its tail.

“Indeed your majesty;” he responded grimly, “the taking of Babylon will be no easy matter; her walls are of baked brick and they are very high and very strong…“

“Hmmm“ Cyrus hummed thoughtfully; mentally reminding himself that it was his extremely cautious nature which made Hystaspes such an efficient general. And he was right about the Assyrians taking a defensive position behind Babylon’s reputedly invincible walls; he was quite sure that will be exactly what they would do. What neither they nor Hystaspes knew, however, was that Cyrus had already learned of a weak spot in her defences. He had said nothing of this to anyone, fearing that if the enemy should get wind of what he was planning they would simply take steps to circumvent it. But, just to put the poor puzzled Hystaspes out of his misery; at least to some degree; he said enigmatically, “That’s true Hystaspes. But perhaps their very strength may prove to be their undoing!”

Now Hystaspes was genuinely relieved; he had no need to know what Cyrus’ plan was for the taking of Babylon; he merely needed to know that his king actually had a plan. And although he could make little sense of this, his king’s latest utterance, yet he was quite confident that it made perfect sense to Cyrus, at least; and that was all that mattered. Indeed, Hystaspes now thought that his king and emperor certainly seemed to know exactly what he had in mind; and if he said nothing further about it, Hystaspes knew now that this was because of the need for secrecy and not for want of a plan.

*** ***** ***