Tags

By Neville Cole

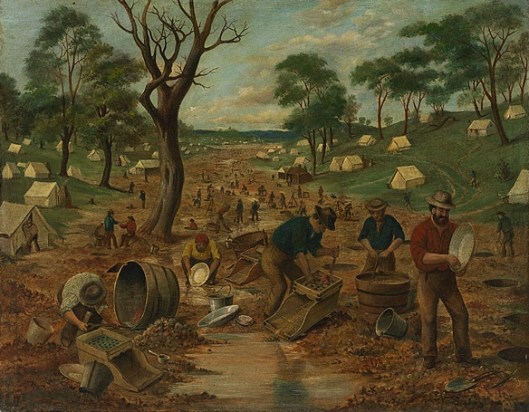

The beautiful English home on the hill that had been my grandfather’s pride and joy was gone. All that remained was the stone hearth and chimney that my father rebuilt and tended to as if it were my mother’s earthly tomb. The years that followed, my brothers recalled, were unrelentingly difficult without a hint of a woman’s touch. Although my father still had money remaining from his father’s glorious golden days, we, his kin, lived as feral outcasts in a one-room miner’s shack by the tapped out stream at the bottom of the hill. My father brought a goat to replace the mother’s milk my colicky lungs cried out for and later he purchased a few hundred head of sheep and turned my brothers into unwilling shepherds. The parties, gaiety, and gatherings of neighbours ceased and we became known collectively as the “wild Moores of Ballarat.”

My father turned quickly to drink as his only consolation. His chief bursts of productivity coming once a year at shearing time when he worked almost around the clock until all the wool had been clipped and bagged. Then he would be gone, sometimes for weeks at a time, to Melbourne to sell his measly wares for the best price he could muster. But later, on quiet evenings in the shack, before the spirits turned his heart as dark and cold as a mid-winter storm, he would tell us stories of his father Samuel, the lucky Moore from Kilmarnock.

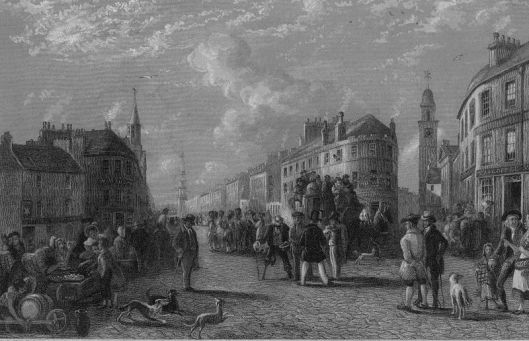

“Your grandfather came from the land of Robert Burns and Walker’s Kilmarnock Whisky,” he would always start as if the jug in his hand was drawing the story from the depths of his soul. He was the luckiest man who ever lived,” he would add with the bitterest of smiles. “He turned his back on the land of the true Moores and laid plans to come to this godforsaken plot as soon word of Edward Hargraves’ find at Ophir spread across the globe. Of course, by the time he made it to these shores, Ballarat was the center of the universe and the lure of golden riches drew him here as surely as the sun holds us all in orbit. He was barely twenty years at the time with little education and no discernable skills but he soon learned he had a nose for gold to go along with his limitless yearning for adventure. He was also the unsung hero of the Eureka stockade, lost to history, but were it not for your grandfather we may not be now be living in a free Australia. For you see, it was your grandfather who saved the life of one Peter Lalor.”

How my grandfather Samuel came to the rescue of the first outlaw to make it to parliament is a story of reckless bravery and frankly impossible luck. It all began soon after his arrival when he fell in, quite literally, with another young Scottish miner named James Scobie. The two met, as most miners do, at a hotel when Samuel stepped between James and the hotel’s proprietor, a Mr. Bentley, during a confrontation over an apparently unpaid tab. Samuel was knocked unconscious and woke up later outside in the dirt being tended to by a grateful James Scobie. Now you may think that was a rather unlucky beginning to what I proposed was a story of remarkable luck; but taking a billy club for a stranger can tend to forge a quick friendship and James and Samuel became mining partners shortly thereafter and thus my grandfather began his trek down the often hazardous path of the gold miner in earnest.

James Scobie was a fine miner but as pig-headed as the day is long. He and Samuel continued to frequent the Eureka despite the constant threat of bodily harm from Mr. Bentley. As the months and years passed, Samuel began to suspect that the reason for their almost nightly visits to the Eureka was due to more than just a taste for whiskey and rum; he noted that James attentions often fell upon the proprietor’s comely wife, Catherine. These attentions, Samuel recognized most likely accounted for Mr. Bentley’s simmering fury every time this usually free spending and frankly mostly trouble-free customer walked through his doors.

Lucky for him, Samuel was not with James as he wandered past the Eureka hotel during the early morning of October 6, 1854. If he did it is quite possible he too would have been found face down in the dirt with a fatal battleaxe wound to his head. Samuel attended the hasty trial that took place that very afternoon when the local magistrate acquitted Mr. Bentley for lack of evidence, even though witnesses saw Mr. Bentley on the street with three other men and a woman at the time of the murder. It was noted that a woman, believed to be Catherine, was heard to exclaim “how dare you break my window.” It would not be until many years later that Samuel would wonder just what caused James Scobie to break Catherine Bentley’s window at two o’clock in the morning. At the time of the trial all he could think of was revenging his good friend’s death.

It was Samuel that took the lead ten days later when a reported 10,000 miners took to the streets and burned down the Eureka hotel while James and Catherine Bentley fled for their lives. Again, due mostly to luck and partly to his quiet, unassuming nature, Samuel was not among the nine miners arrested over the next few days for starting the fire.

The miner’s anger turn quickly to political revolt and Samuel too was present at Bakery Hill to vote in the resolution “that it is the inalienable right of every citizen to have a voice in making the laws he is called on to obey, that taxation without representation is tyranny“. The group also resolved that day to secede from the United Kingdom if the situation did not improve.

The mood of the Ballarat miners reached its feverous peak on 16 November 1854 when Governor Hotham appointed a Royal Commission on goldfields problems and grievances. But as history has shown us, authority rarely bows out of a bad situation gracefully and Commissioner Rede’s response the governor was to ignore the grievances and instead increase the police presence in the gold fields and summon reinforcements from Melbourne.

How Samuel avoided arrest and death during those revolutionary days can only be attributed to pure luck. After all, he was one of the first of the miner’s to pledge open rebellion and burn his mining license and he was among the mob that surrounded arresting officers conducting a license search the very next day. He was present at the unfurling of the rebel Eureka Flag and part of the mob who swore the oath of allegiance to it. “We swear,” they spoke as one, “by the Southern Cross to stand truly by each other and fight to defend our rights and liberties.”

The tragic events of the battle of the stockade have been well documented; it is now known how what had at one time been a force of 1700 men dwindled to a mere 150 miners on December 3rd, 1854 when most of the miners at the stockade returned to their tents under the assumption that the Queen’s military forces would not be sent to attack on the Sabbath.

Samuel was one of the 150 who remained when a party of 276 police and military personnel under the command of Captain J.W. Thomas approached the Eureka Stockade and a battle ensued. The ramshackle army of miners was hopelessly outclassed by the well-trained military regiment and was routed in about 10 minutes. But it is his actions during that 10 minute battle for which Samuel ought to be legend; for it was he who hid Lalor, arm shattered by musketshot, under a pile of timbers. Samuel then somehow managed to stay nearby undetected while the victors removed the dead from the stockade. He could see blood trickling from beneath the pile of slabs where he had Lalor hid; but while soldiers, keen to capture Lalor were still in the stockade, Samuel dared not make a move. That is, until the last of soldiers had left. Then he quickly stepped back into the fray and smuggled Lalor away, put him on a horse, and sent him off to eventual safety.

Now, I’m not here to pretend that it was an easy escape for Lalor. We all know well that over the following weeks he had to survive several near captures and undergo two amputations before he would be truly free; but the fact remains that, without my grandfather, Samuel Moore, he never would have survived the stockade. Without my grandfather, Samuel Moore, the near 50 year trudge to independence that followed would have surely been without one of its most passionate and influential leaders. For the lucky Moore from Kilmarnock it was just one of a hundred such times during which he tempted fate and won. If only my own father had just one tenth of his father’s good fortune my early life would have been quite different indeed. Then again, perhaps luck, like many other genetic traits, tends from time to time to skip a generation.