Story by Warrigal Mirriyuula.

Pat Hennessey the Fire Warden was walking over as Chook pulled off the highway up through the road gate in the Police Ute. The building had been almost entirely destroyed by the fire and a plume of grey and black smoke was drifting into the sky. The rain had stopped and the clouds that had hung low over the district all day were now beginning to slowly clear. Chook got out and dragged his Wellingtons from the back of the ute. As he undid his bootlaces Pat filled him in.

“Thanks for comin’ out Chook. I would’na ordinarily bothered ya ‘cep’ this isn’ what it first seems. Now that we’ve got the thing pretty much out we’ve found some things about this one that aren’t right.” The warden paused. “For a start we’ve got a body.”

That got Chook’s attention. He quickly looked straight at the warden as he pulled the left Wellington on. “A body?”

“At first it just looked like an outbuilding fire with a few dead sheep but, yeah, then we found the body. Ya better come an’ ‘ave a look.”

The warden turned to walk up the muddy path to the remains of the burned outbuilding. Chook didn’t like the sound of this and the sight of Bagley standing off to the side, his hat dripping and his driz-a-bone glistening in the rain, his arms crossed and a foul look on his face didn’t auger well. Chook pulled on the other boot and followed after Pat.

As Chook caught up to the warden the building was still just alight in spots, tiny flames leaping like dancers across the charred timber. Most of the ruin was smoking and steaming as the firemen played water over the blackened mess. There was the distinct sickly stench of burned wool, sheep flesh and diesel.

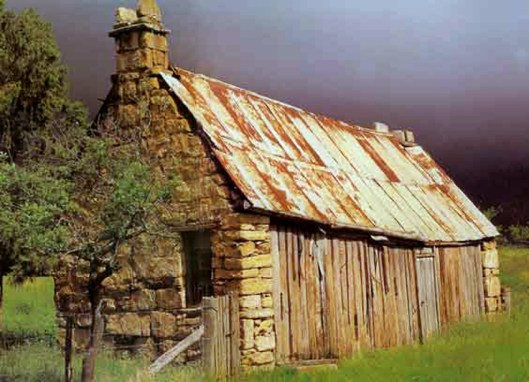

The smoking pile had been used to store feed and hay, odd tools, discarded machinery and obviously fuel for the tractor. The foundations, floor and gabled end walls of the building were constructed from local rubble blocks mortared with lime cement made from Molong limestone. The front and back had been timbered with thick axe cut slabs. An iron roof had replaced the original Sheoak shingles over the rough timber trusses. It had survived for well over a hundred years, an iconic piece of bush architecture, a practical and pragmatic building from the very earliest days of white occupation. The stone and heavy timber walls providing some security for early shepherds worried about aboriginal attacks as the white man’s mutton invasion continued inexorably into the Wiradjuri lands beyond the early colony’s Limit of Settlement.

The roof iron had collapsed into the building and lay, twisted, still hot, amongst the ash and charred wall slabs, roof beams and trusses. The carcasses of the dead sheep lay in a deep bed of ash, all in one corner where they had no doubt retreated from the flames only to be trapped and burned alive. Chook noted they had been rams, the blackened bony cores of their horns clearly visible. Chook felt a shiver run up his spine. Were these the prize Merino rams that Bagley claimed had been interfered with? No wonder Bagley looked dark. This could put a whole different complexion on the day.

As Chook followed the warden around to the rear of the building the smell changed and then there where the wall had partially collapsed out, Chook saw inside, the body; only the head and shoulders were visible, all tangled in charred timber and bent iron, the head reduced to a leering skull with adhesions of cartilage, charred flesh and burnt hair. The eyes had cooked in their sockets. The lips, shrunken back revealing blackened gums; the teeth, big, strong and dazzling white against the black, gave the appearance that the skull was laughing hysterically. Chook gagged and shivered again. It was unsettling, gruesome to look at. This burnt offering had once been a human being.

The warden stood back as Chook tried to get a better look at the corpse. He leaned inside the wall line. The whole business was still smoking and the smoke was getting in Chook’s eyes. He pulled his head away, his eyes watering. He reached out to get his balance and leaned on the rubble-stone wall. The stone was still uncomfortably hot and Chook pulled his hand away too quickly, loosing his balance and falling on his bum in the mud.

“Bloody fantastic!” said Chook, getting up to wipe the mud of his uniform serge.

“Yeah, we’ll have to wait until the whole thing’s cooled down before we can get the body out.” the warden offered a little too late for Chook’s griddled hand and muddy bum.

“Yeah, let’s do that.” Chook said sourly, but enjoying the soothing relief the mud was providing his hand. He waved it around a bit.

“Listen, has Bagley offered anything on the cause or nature of the fire? Bagley was still pacing some way off, his face a mask of dark animus.

“Hasn’t said a word mate” pulling his head to one side, chin in, and looking at the ground. “Not a dicky bird.”

Chook’s eyes narrowed and he looked over at Bagley. “That’s not like him.” His gaze stayed on Bagley.

“No mate it’s not.” The air between the men thickened with suspicion as they both kept Bagley in their gaze. “Once ‘ed arrived I expected to get chapter and verse on fire fighting delivered in the usual style.” The warden paused and looked at Chook. “’e ‘asn’t said a word, to anyone. Not a word. He’s just stood there were ‘e is. Highly unusual I’d say.”

“So he wasn’t here when you arrived. Who reported the fire?”

“Miss Hynde at “The Pines” over on the other side of the valley.” The warden pointed to a cottage about two miles away on the opposite side of Molong Creek, nestled in a corner where two tall stands of old Monterey Pines met. The little white house was magically aglow in the deep dark green of the pines, at that moment illuminated, picked out in a beam of sunlight breaking through the dispersing rain clouds. “You can see the whole valley from her place.”

Chook was momentarily transfixed by the uncanny scene. He shook his head and deliberately looked at Pat.

“Does Bagley know about the body?” Chook looked back at Bagley.

“Well the men got pretty excited when they first saw it. There was some shouting and hoying but I don’t know whether Bagley knows or not. Like I said, ‘e hasn’ come any closer than “e is now since ‘e arrived.”

The fire was out and the rest of the fire crew had begun to rake out the embers to spread the heat and hasten the cooling. They were about to start pulling off the crumpled iron when Chook shouted for them to stop. The firemen stopped and turned looking to the warden for direction.

“What’s on ya mind Chook? The warden asked while the men waited.

“Something about this doesn’t sit right.” Chook said with classic understatement. He took a good long slow look around the area. “Look it could be anything at this stage. Misadventure, suicide, manslaughter, or it might be murder. I’m gonna have to call it a crime scene anyway, so no one touches anything until I can get the Inspector out from Orange. How much water have you got left in the tanker? Have ya got enough to just keep damping the hot spots?”

“Yeah, sure; we’ve prob’ly got a couple a hundred gallons left. If we run low we can call the other tanker but I don’t think that’ll be necessary. Why, whata ya thinkin’?”

Chook didn’t feel like explaining himself. He wasn’t sure he could anyway, but there was a growing feeling that the thing better be done by the book. Whatever had gone on here, it wasn’t simple. There was a whole lot more that Chook didn’t know. This was MacGuire’s land, his building; those were probably his rams; which meant Bagley was going to be a fixture of the investigation.

Chook wasn’t certain about what he was thinking and decided that a simple cover story would hold the warden. “Have you met Inspector Beuzeville from Orange? He’s a stickler for the regs. We’ve got a body therefore this is a crime scene until it’s released by the Inspector.”

“Whatever you say Chook.” The warden was happy to be shot of the responsibility of being boss of the fire. It’d save him from having to deal with Bagley. If the police said this was a crime scene then a crime scene it was. Someone else could do the worrying.

“I want your men to pace out 50 yards in all directions from the fire. Then they’re to stay outside that perimeter except for the bloke on the hose and he should try and move around as little as possible. As soon as there’s no more smoke or steam, he has to move outside the perimeter.” Chook looked over at Bagley again. He’d have to talk with him. “I’m gonna have a yack with Bagley then I’ve got some calls to make. I’ll get someone out here as soon as I can, just make sure that there’s someone here all the time until he gets here. I’ve got a feeling in me water about this one.”

“Whatever you say Chook.” the warden said again, taking his cue from Chook’s serious tone. He turned and shouted at the firemen, “Righto, disconnect the pumps, pack it up. Bob you hook up to the tanker and run the little pump. Set ya nozzle to spray and just keep it playing over the hot spots. Mick, you pace out and mark a fifty-yard perimeter; and remember, all of you, don’t move anything, don’t disturb anything. This is now a crime scene, the cops are in charge.” The half dozen young volunteer firemen got to it. Mick was pacing out the perimeter and flagging it with tagged stakes, the others were emptying and rolling the hoses. The one called Bob had reconnected to the tanker and started the little petrol pump. He took up a position on the high side of the blackened ruin and commenced damping down.

Chook walked over to Bagley who had stopped pacing and was looking blackly at Fowler.

“You took ya bloody time Fowler.” Bagley always started every encounter with an insult or criticism. “If you’d been here first thing like I said maybe this wouldna happened.” Bagley let that sink in. “Those bloody rams were worth a small fortune. Every one of ‘em’s a ribbon winner.” His anger and frustration were plain.

Chook wasn’t in the mood for Bagley. He had no patience for the man’s abrasive and insulting way.

“Ya can’t go up there Bagley. It’s a crime scene for the next few days. I’m gonna have ta call in the D’s from Orange.”

“What, can’t handle a little fire Fowler” Bagley smirked.

That was it. Chook had about as much from Bagley as he was gonna take. The man was unfit for civilised congress.

“Look Bagley, there’s a dead body in the back corner. This “little fire” is much more important than the loss of some bloodstock no matter how valuable they mighta been. Bloody hell man, the rams are insured aren’t they?”

Fowler was just hitting his straps. “A man’s dead Bagley. Burned liked a forgotten Sunday roast.” Bagley didn’t react and didn’t seem to care. Just like the bastard, thought Chook.

“You don’t go closer than fifty yards and if I find out you have, then I’ll arrest you for interfering in a police investigation.” Chook looked Bagley straight in the eye “Have ya got that?”

“Ya wanna watch ya self Fowler. I’m not without influence round here.” Bagley threatened, inflated with pride, “While ever I’m manager here I’ll go where I damn well please and do what I need to.”

The fact that a dead man had been found on the property he managed didn’t appear to be figuring in his calculations at this point. To Bagley it was obviously a bloody inconvenience but essentially someone else’s problem. “What about my bloody rams?”

“MacGuire’s rams Bagley. Remember? You’re just the help.” Chook was really getting on Bagley’s tits now, he could see it, and saw no reason to back off. “I’ve had enough of you Bagley. You may think you’re a big wheel round here but to me ya just a bully; a loud mouthed common thug. Those you can’t thump ya threaten. You push ya luck on this and you’ll find out just what the NSW Police are capable of. Have I made myself clear enough now?”

Chook always felt a slow surge of blood when he invoked the brotherhood of the force.

“You’ll regret this Fowler. I’m not a man to make an enemy of.” Bagley was fuming. He spat into the mud, turned and walked back to his Land Rover.

“I’ll need to talk to you later. Make sure you’re somewhere where I can find you.” Chook shouted at Bagley’s retreating back.

“You can go to buggery Fowler. I’m sure you know the way.” Bagley got in the Land Rover and took off down the valley towards the main homestead, on his way to report to MacGuire.

Chook wondered what made a man like Bagley. Even a dead body didn’t move him. He had no friends so far as the Policeman knew; and though he was married, he and his wife had no children. All he had was his job at MacGuire’s, his own high opinion of himself and an indefatigable drive to get what he wanted no matter the cost to those around him.

He was a brutal boss known for violence against casual hands. He’d blinded a young rouseabout in a fistfight when Chook was a teenager. He’d been charged with grievous bodily harm but the charges were dropped when the complainant failed to show for court. There was talk he’d been paid off.

Over the years there had been many stories of Bagley’s cruelty and he reserved a specially callous contempt for the Fairbridge boys he took on, treating them little better than the animals themselves and reminding them all the time that they were the waste and detritus of the empire and they should be bloody grateful he employed them at all. In short he was a shit of a man in Chook’s opinion, and this investigation was going to be all the more difficult with him involved.

Fowler got on the radio in the ute and contacted the station in Orange. He made a quick report to Inspector Beuzeville who agreed it was suspicious and that it should be looked into more thoroughly. He couldn’t come right away; he’d be out at 6AM tomorrow morning. Best to get the body out before the heat of the day. In the mean time the Inspector told the Sergeant to secure the scene, cover the body as best you can and no one to touch anything, he’d bring the Coroner’s Pathologist and a police photographer with him, “Over and out.”

Chook got out of the ute and walked back up to the burnt out building. He told the young fiery that he had to go into town but that there’d someone back in an hour to relieve him. The young bloke just nodded as he distractedly continued to hose the sodden remains of the building.

Chook got in the ute and took off back into town. The sky was now clearing rapidly and the road was steaming as the afternoon sun came out from behind the clouds. There were still several hours of light yet and there was a lot Chook wanted to get done before Beuzeville came out in the morning. He’d get young Molloy to sit the night watch at the scene, Chook wanted to talk with Miss Hynde and he’d have to beard Bagley at home; and just to be sure he’d talk to MacGuire too, if he wasn’t down in the smoke.

This was more like it, Chook thought. Real Police work, hopefully with a real outcome. This wasn’t dealing with drunks or scolding kiddies, or another turn in the eternal dance with Jack. This was meat and potatoes Police work.

There weren’t that many bodies turn up in Molong in suspicious circumstances and Chook always took these cases very seriously. People needed to know what happened and the dead man, lying in the cooling ruin, that horrible skull silently screaming for justice, he would have one last mate and Chook wasn’t about to let a mate down.

Chook realised at that moment that though procedure required an open mind, the gut feeling that was developing deep inside him was insistently shouting “foul play”. Chook had learnt young not to deny his gut feelings, but what had exactly gone on here was still a mystery waiting to be deciphered.

Chook put his foot down and for the first time in weeks turned on the siren.

We are so lucky not to live in slab huts with hand powered washing manglers or whatever they called them. Of course the huts are fantastic. To look at. Or when modernised to the point of comfortable liveability, which I have no doubt the Oosterman owned one is. Have you seen those little whitewashed Irish cottages? Cute as all hell, but to live in? With ten or more living children? Pass.

LikeLike

Flan O’Brien’s “The Poor Mouth” has a fantastic description of the drunken grandfather of a dirt poor Irish family asleep before the fire, his boot leather smoking while a pig slops up the spilled whiskey and a babe in swaddling, filthy from the ashes, plays games with the cinders.

He also goes on to describe what may well have been the first flush of gentrification of those crofter’s hovels as the wealthy looked for holiday homes in the more remote parts of Ireland.

It’s a very funny book.

LikeLike

Gerard had a story here called ‘Dalliances and Dunny men’. It was accompanied with a photo that he took of our neighbour’s little slab hut.

For the life of me I can’t find it; I was going to ask Waz to have look at it.

The story is still on his own blog but the picture is gone. As it was his own work, there can’t be any copyright problems !

Oh well , he must have deleted the pic accidently…the one here from Berrima looks most charming.

LikeLike

Warrigal, if you are interested, have a look at our neighbour’s little slab hut. You’ll find it under ‘The Mens’, Rooms at Pig’s Arms.

Thanks, Emmjay.

LikeLike

Yes, I remember it slowly subsiding into the earth. The best of the remaining huts have that lean to them. It’s the result of the construction method.

LikeLike

Chook suspects fowl play?

Well, you knew someone would have to say it. 🙂

LikeLike

I watched that show on the Wood Royal Commission on the ABC last night. Apart from reminding us all how ugly it got inside the force in those days,proving that NSW has always had the best force money can buy, it also documented the criminally corrupt activities of a certain Detective Inspector Fowler.

You may remember him from the surveillance vision as the shorts wearing corrupt copper with the fat knees taking possession of fistfuls of fifties whilst trying to work all the variants of the word “fuck” into every sentence he uttered.

It turns out he was known as “Chook”.

What I’m trying to work out is whether or not I heard the name back then and have unconsciously used it now, or whether the probability of any one called Fowler ending up with the nickname “Chook” is so high that were I to have given him another name it wouldn’t have sat right.

It’d be interesting to know how many male Australians with the Fowler surname have been called “Chook” at some time in their life. I’ve known several. Like red heads called “Bluey”, they’re everywhere.

LikeLike

Waz, there is no person called Fowler who lacks the nickname “Chook”. The species simply does not exist.

In my HSC I did First Level Biology amongst other stuff. One other dude also did Biology L1. His name was Chook Rowlands – because he had a few pet chooks. I think his real name was Kevin. So whereas all Fowlers are called “Chook”, not all “Chooks” are Fowlers.

Avian logic !

LikeLike

If this keeps up we may need to get our “fowling pieces” out. Purdey make a nice “410” long barrel over and under “fowling piece. I know Merve was eyeing it off in the catalogue the other day when I dropped in for a beer and some wedges.

LikeLike

So it was “Purdy” nice !

LikeLike

It was purrrrr’fect Darling, simply purrrrr’fect!

LikeLike

…what about Alice?

LikeLike

Apparently you’re not the only one with this fixation on Alice. Nicky Chin and Mike Chapman were similarly smitten. It must have been while Alice was living in the Nurses Home at RPA.

The “Alice Effect” was immortalised in their famous song,

“Living Next Door To Alice”

Sally called when she got the word,

She said, I suppose you’ve heard about Alice

Well, I rushed to the window, and I looked outside

I could hardly believe my eyes

As a big limousine rolled up into Alice’s drive

Don’t know why she’s leaving, or where she’s gonna go

I guess she’s got her reasons but I just don’t want to know

‘cos for twenty-four years I’ve been living next door to Alice

Twenty-four years just waiting for the chance

To tell her how I feel and maybe get a second glance

Now I’ve got to get used to not living next door to Alice

We grew up together two kids in the park

We carved our initials deep in the bark, me and Alice

Now she walks through the door with her head held high

Just for a moment, I caught her eye

A big limousine pulled slowly out of Alice’s drive

Sally called back and asked how I felt

And she said, hey I know how to help – get over Alice

She said now Alice is gone but I’m still here

You know I’ve been waiting for twenty-four years

And the big limousine disapeared

Don’t know why she’s leaving, or where she’s gonna go

I guess she’s got her reasons but I just don’t want to know

‘cos for twenty-four years I’ve been living next door to Alice

Twenty-four years just waiting for the chance

To tell her how I feel and maybe get a second glance

Now I’ve got to get used to not living next door to Alice

No I’ll never get used to not living next door to Alice

LikeLike

Last time I heard that it had morphed into, ‘Living Next Door To Alan (BOND)’.

LikeLike

Bring back Alice

LikeLike

Keep ya shirt on…., she’ll be back shortly, alright?

LikeLike

I’m with HOO!

Alice, not Alan!

LikeLike

Just don’t tell Tutu

LikeLike

How does Tutu put up with that face?

LikeLike

No idea, poor girl

LikeLike

The posts seem to have a life of their today, not listening to me…

LikeLike

Big M, we put three skylights in our Balmain house and the same number here on the farm, plus we replaced some corrugated iron sheets on verandah roof with polyurethane ones to let in more light.

Afterwards I plant trees and other greenery that take away some sun… 🙂

LikeLike

When you look at our slab hut at:

http://www.stayz.com.au/17027

you can see a plate covering the outside of the chimney. We are told that this would allow the fire to be stoked from ouside as well as inside.

We had some old relatives giving scant information on how they lived in this slab hut, but not many are still alive that could give a clear picture. We have an old grave on the property, but even here there are conflicting stories: an adult having drowned on his horse crossing the river, the other, a baby drowned while mum was doing her washing in the river. A blind lady lived there with nine children who died in 1972 in Goulburn Hospital. A while ago, an old man visited us and the cottage together with other relatives. He stood just outside looking at the hill. He never went inside.

I find that stuff fascinating but Helvi prefers the ‘living’ part more.

LikeLike

Possibly also to rake out the spent ashes from the outside obviating spills and ash contamination indoors. Ash, particularly fine ash, was a useful resource and was used to make soap and as a binding agent in bush plaster.

LikeLike

I should have mentioned G that the slab hut above is from down your way. It’s located at Berrima.

LikeLike

I agree, Helvi, why install a modern fireplace, then have the flue go straight out the wall? Then again, here in Newcastle you see some funny things, west facing skylights, houses with no windows on the northern face, solar panels on the western hip of the roof, etc, etc.

LikeLike

I leave the body to Foodge and co and move to inspect the hut…

Why is the main part of the fireplace always outside, the bricks or rocks would heat the hut better if inside ? Our cottage has been braced against Southern Tablelands winds with flattened kerosine tins and wallpapered with newspapers for extra insulation. Mrs Leah had nine children; we have had some visits from her living relatives. Gez loves all that old stuff as you might have noticed..

LikeLike

Many of the early slab huts that were made of materials other than stone included a fireplace/stove that sat in a box constructed external to the walls of the hut. The chimney was often not integrated with the main body of the building to avoid the spread of flue fires to the timbers of the roof. It meant that you could fight any chimney fire from both inside by throwing water on the seat of the fire; and outside by putting water all over the fire box and chimney. It also made a huge difference in summer when the fire still had to be lit to boil water and cook the basic food items like bread, porridge and mutton, mutton and more mutton.

The fire box, being in a sense another small room, allowed the heat to be dissapated through flaps that were opened to allow the cross flow of air.

In buildings where the fire box and chimney are constructed from stone this was less of a problem but stone buildings still burned down when the often poor mortar was cooked out from between the stones and tongues of fire found there way to some wooden part of the building.

One of the things that strikes you as you read back into the past is the number of fires and deaths in fires. A natural consequence in a world built predominantly of wood.

LikeLike

Thanks Warrigal,

My dad was a fireman, so I have an ongoing fear of:

Deep frying food, at home.

Candles, lanterns, etc, inside.

Fireplaces, particularly in timber cottages.

These, plus smoking in bed, were the causes of most fires which Dad attended.

Often mortar was almost all sand and lime, with very little cement. This came to light fairly graphically after the infamous Newcastle earthquake.

LikeLike

I no longer fear fire. I am fire. I have become the flame, elemental, all consuming! The world burns before me…………..

Opps, did I actually type that?

LikeLike

Yeah, yeah, sure thing Waz.

LikeLike