By Warrigal Mirriyuula

Benjamin and Edward were brothers. They were the identical twin sons of Maeve O’Sullivan and Daniel Fitzpatrick. This is their story.

The twins were an unexpected and somewhat difficult blessing that cold December morning when Maeve went into early labour in the tiny workers cottage where the family lived in Gateshead. At first, given their prematurity, the twins were not expected to live.

It was a mercifully brief labour. The midwife, looking upon them after she’d cleaned, swaddled and laid them, one on each side of Maeve, thought of the sadness that would come in train of this cold windy beginning with the slates on the roof rattling out their tattoo of stony cold welcome. These plucky little boys would be lucky to see the week out. She took Maeve’s limp exhausted hand in hers, put on her best, most brave smile and said, “Two strong sons to look after you and Danny. You’ve done so well for one so young and your first time too”.

Nodding vigourously to confirm the truth of this statement, she turned away and busied herself tidying up the room. She stoked the little fire in the iron grate and added another lump of coal. By the time she turned her attention back to Maeve the young mother was asleep and the baby boys, faces red and still showing the creases and folds of the newly arrived, fisted little hands and their eyes screwed shut, made the best they could of their first day on earth.

Maeve did washing for the posh, and a little needlework when she could get it. A native of Skibbereen, Maeve’s family had come to Newcastle in search of work for her da. He’d got a job at a nearby pit

Maeve met Danny on a works outing when she still had a job in the bottle washing plant at the Newcastle Breweries. She had been sixteen when they met. Danny, an orphan from Belfast, was nineteen and worked on the docks and in the warehouses along The Tyne, taking what work was offered and drinking most of his pay. Indeed he’d been drunk the day Maeve first set eyes on him.

Still clutching his bottle of Brown Ale, he was throwing up and admonishing himself all at the same time. Maeve didn’t know what to make of this untidy apparition as she looked down between the refreshment tents. There he was, barely upright, amongst the crates and strewn empties, the ropes and pegs, half full bottle swinging loosely at the end of his arm while his other hand tried valiantly to keep his glossy black, curly fringe out of harm’s way. Between goips he smiled so sweetly at Maeve, like an angel; and so honestly, without a hint of self-consciousness in his bright green eyes.

“Musta got a dirty bottle.” he slurred in a tone that fully confirmed that his current situation was in no way his fault. Indeed it wasn’t the drink at all, or even the surfeit of it, but a dirty bottle, no question.

Maeve let go a spontaneous laugh before her face assumed a more utilitarian look of mock outrage.

“I wash them bottles!” she said with just a little more self-importance than she intended; or was due so ordinary a job. Danny shrugged, smiled sweetly again, then turned and spat into the grass. He straightened himself to face Maeve, his black curls in his eyes.

The men in Maeve’s family were always drinking so the sight of this good-looking young man drunk in the middle of the afternoon was nothing new or extraordinary. It was a brewery picnic after all.

“Here, gimme a look at ya” she said bossily as she stepped over the guy ropes to join him between the tents. “Let’s get this mess off ya.”

Maeve helped Danny right himself and wiped his mouth and face with a little spit on her favourite cotton handkerchief. The one she’d embroidered so carefully with the little swallows and blue birds. She’d wash it out when she got home. She folded the messy stink into the hankie and tucked it back under her cuff.

Danny, unused to such tender ministration, simply dragged his coat sleeve across his mouth and inspecting it blearily, seemed somewhat perplexed to find no evidence of his late indisposition on the coarse wool. Maeve felt then that she would like this drunken young angel; and Danny, looking at her really for the first time, believed he might have discovered something more intoxicating than drink.

The rest of that summer they spent as much time together as their work and Maeve’s parents would allow. Friends said of them that they were made for each other. Danny’s thirst for the drink seemed to abate. He believed he’d found a good hearted country girl who accepted him for what he was, and Maeve’s friends wondered how long it would be before Danny put the whole thing on a more matrimonial footing.

That would have to wait however.

In September, as the leaves were turning and falling, Danny got a berth as a general hand in a steamer on the Australia run. Maeve’s mammy and da thought just as well. She was only sixteen and Danny wasn’t exactly the match they’d hoped for. He was a good enough young man and he doted on their Maeve, but he drank too much and at such a young age. Perhaps the hard work and discipline at sea would knock some responsibility into him. They hoped for the best for their only daughter.

Danny had first laid out his plans for Maeve and himself one evening as they shared a late cup of tea in a café.

As a treat in the midst of their austerity they’d been to see the new talkie “Blackmail”, at the refurbished Stoll cinema on Westgate Road. Before they went in it was obvious that Danny had something on his mind and to make things worse, during the film Maeve just couldn’t feel at ease. She was distracted by the sound of Anny Ondra’s voice. It just didn’t fit. Sometimes Maeve thought it was someone else’s voice altogether. Besides, people didn’t really behave like this. Well, no-one she knew.

Danny didn’t seem to notice it though. He’d sat, wide eyed, transfixed by the new wonder of sound. Maeve loved his boyish enthusiasms and remembered fondly the day they’d walked some miles along the Durham Road looking for a likely hilltop from which to fly a kite they’d made. It was put together from salvaged brown paper and some willow sticks Danny had dried and then shaped with his penknife. Maeve had made the flutters for the tail from scraps of silk in her sewing box. It had been their first family project, of sorts, and during the making of the kite Danny had shown his serious side. As the chief designer and engineer of the kite he’d directed Maeve in a rather stern manner. His own commitment shown by the appearance of the tip of his tongue, slipping out between his lips on the right side of his mouth as he applied the glue to the brown paper and folded it over the springy willow frame. His reserve when they met outside the cinema, put aside as they sat through “Blackmail”, indicated that whatever it was that was on his mind, it had to be at least as important as the kite.

Oh, but it had been great fun that afternoon. Just a couple of kids in the wind blowing over the rounded hilltop, catching the kite and drawing it high up into the blue arc of the sky filled with fluffy white clouds. Maeve imagined herself and Danny riding the kite through the fat clouds, a sort of cumulo-nimbic inspection with Danny as the exuberant comptroller and she as his avid assistant. It was a glorious afternoon.

As she sat in the darkened cinema watching Danny’s rapt attention to the screen she found her apprehension regarding whatever it was that had been distracting him earlier had completely passed away. She squeezed his hand in the dark and he didn’t seem to notice, so completely was he captivated by the screen. Whatever was on his mind, he’d tell her later.

Danny’s plan, as laid out between excited slurps on his tea and interrupted with flashes retelling the film, was to work as hard as he could, spend as little as was possible and put together a nest egg. Maeve would do the same. When they had put enough aside they would get a little house and their life together would begin. The only thing that seemed to be lacking as Maeve’s mind went off into other clouds of puffy possibility, was an actual proposal of marriage. Danny had managed to describe their current understanding and feelings for one another quite well, if a little dispassionately. Maeve had put this down to his wanting to be serious about his life changing plans for them both. He had then recommenced the narrative of his plan at some point after the wedding when they were already set up in their own little house, perhaps assuming that these details would somehow take care of themselves in the living of it. It certainly didn’t seem important to the telling. Maeve had thought this to be just like a man. The ceremony, the satin and lace would be entirely Maeve’s concern.

That was their plan as Maeve farewelled Danny on Tyneside with the wind and the cold October rain flying in sideways off the North Sea. The miserable cold of their parting did nothing to damp the warm glow Maeve had begun to feel about her life and her future with Danny. More sure of herself than at any time since leaving Cork with her family, she saw her future as assured; Danny had almost given up the drink and he would become a hard worker who might turn his personable nature into advancement for himself. Maeve for her part would bear them many healthy children and keep a happy, tidy house with a welcome for all at the door.

That was how she saw it and was working towards that future when Danny’s first letter arrived postmarked Aden. He wrote of how he missed her and of the hard work on board and how his foreman drove him and the other first timers to exhaustion. He wrote of the voyage across the Mediterranean and down the Suez Canal. He said he wanted to describe everything for her and how exotic so much of it was for a young man out in the wide world for the first time.

The words, scrawled in his spidery ill tutored hand, written lying on his bunk with a borrowed fountain pen, filled her heart and she saw, in the dreamscapes she built with Danny’s detailed descriptions, the flying fish leaping across the sparkling blue Mediterranean while the seabirds followed the ship; she saw the colourful ports and the strange people. These sun drenched visions kept her warm as the bitter northern winter set in.

Maeve took to wearing Danny’s rough woollen coat around the house. The one he’d been wearing the day they’d met. She told herself that she could feel, as if from inside it all, the strong contours of the muscles of his back and shoulders. She could smell him in the coat. She shivered a little in excitement and anticipation. Each night as she sat by the small fire doing her needlework in the parlour, too grand a name for this pokey little front room, she would dream of Danny, casting him as a swashbuckling pirate or brave naval hero. All of these dreams ended with Danny running up the quay, tossing his seabag aside, grasping her about the waist and throwing her up into the air; then, slowly, gently, allowing her to slide down the facing of his donkey jacket until their lips met and the reunion exploded into a passionate embrace ending with a long kiss as they both, entwined, turned slowly on the slick cobbles of the quayside.

Late one evening she became so distracted by her reverie that she pricked her finger with the needle and looking, discovered that she’d made a hash of the work and would have to unpick the lot and do it all over. She threw a few pieces of coal in the little grate and began again. A small inconvenience when balanced against her vision of their future.

Danny’s next letter arrived postmarked Goa. Danny said that the crossing of the Indian Ocean had been stinking; hot hard work during the days and sweltering sleepless nights with no breeze. Below decks tempers flared and apparently the Chinese cook had taken it into his head to murder one of the stokers with a meat cleaver. Maeve was shocked and worried for Danny.

“All Chinamen are mad.” Danny had written, as if that explained the whole thing, but that wasn’t the end of the story.

Danny had intervened as the stoker ran down one of the companionways with the cook close behind. Danny tripped the cook who went sprawling at the bottom of the steps, dropping the cleaver. There’d been a scuffle for the intended murder weapon and Danny’s hand got a grip first, but his grip didn’t quite close and the cleaver slid through a scupper, tumbling down the side of the ship before sploshing into the sea. The stoker disappeared round a corner while Danny got up and wiped himself off. The cook, thwarted in his murderous ambitions, spat vehemently over the side and fixed Danny with an inscrutable oriental eye; apparently he only had the one, before turning and walking off down the deck muttering violent curses only he and his malevolent gods would understand.

The mate had fined Danny 10/6 for the loss of the company’s cleaver and cancelled Danny’s next shore leave. Apparently the cook was mad, but he was a great cook and the First Mate, looking to cool the whole thing down, decided that on this occasion he’d adjudicate the matter as black and white letter of the law. It was Danny’s hand last on the cleaver, it was Danny tripped the cook. The stoker wasn’t called and nobody wanted to deal with the mad Chinaman.

Danny had thought this grossly unfair and told Maeve so in terms that carried the salty smell of the sea right off the paper.

With his next letter from Singapore his mood had blackened. There were no fanciful descriptions of the foreign and bizarre, no tales of sunlit seas and far blue horizons. Just a withering tirade against the mate and his foreman, who Danny wrote “treats me like a slave; and he’s always pushing and kicking the new hands. He’s a ironclad bastard, if you’ll excuse my French!”

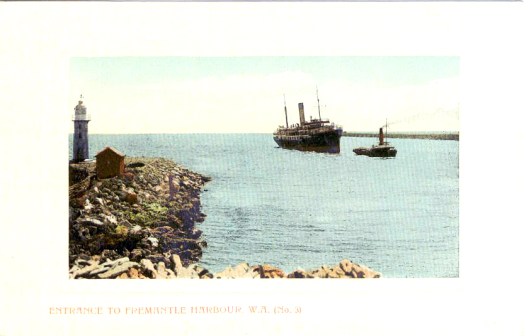

She got only a postcard from Fremantle but Danny promised a long letter from Adelaide. It didn’t come.

By the time Danny’s letter from Sydney arrived Maeve had some bad news of her own for Danny. The financial collapse soon after Danny’s departure to sea had seen Newcastle Breweries sack many of its workers; “last on, first off” had seen Maeve lose her job. Her two elder brothers had been laid off too and the family was struggling on only Da’s wage and the little bit Maeve and Mammy brought in from needlework. The brothers were out every day, trudging up and down the waterfront and the warehouses along the Tyne trying to pick up work. As demand for coal dropped, so too the pits began to put men off and Maeve’s Da hoped he could hang on to his job but it seemed the whole town was now unemployed.

Maeve so needed to talk with Danny. She badly needed his old optimism but she had no idea how to contact him other than through the shipping office down on Tyneside. It was only a mile from her home in Gateshead down to the docks so she walked. When she got there one of the shipping clerks told her that apart from radio telegraphy, which she simply couldn’t afford, there was no way she could contact Danny until he would be almost home, and that might be another three or four months depending on cargo and whether they came back via the Cape or Suez or went across the Pacific and through the Panama Canal. The clerk, seeing her distress, took pity on Maeve and offered, “If you come back in a few days we’ll know which way the ship’s going and you might be able to send a letter “Post Restante” to a port along the way, but the seaman would need to know and pick it up. Do you think he’d do that?” It was the best he could do. Maeve was disconsolate. She thanked the clerk adding, “It’s silly, I’m silly! We didn’t make a way for me to write to him.”

She thanked the clerk again and began the walk home, her eyes filling with slow tears. Suddenly she felt as if the bright future she and Danny had planned was in dire peril. With her out of work she couldn’t continue to put that little by each week. Indeed all her savings were going on keeping her own family ahead of the landlord and the sheriff. Uncertainty began to dog her every thought. She abraded herself for not thinking that, of course, she’d want to write to Danny. “That’s what comes of too much daydreaming.” she thought, as a coolness crept into her and she began to doubt herself, Danny, and the future.

yo

LikeLike

Wow! That’s seriously good, Warrigal. Approaching your own high standards, even.

LikeLike

Thanks for that. Not quite right, but its not bad is it? And it just came out like that.

Dolly’s response was the same when I showed it to her.

I’m dead chuffed actually, and there’s more coming all the time.

LikeLike

After leaving Rotterdam 1956, our first stop after Napels and Messina was Port Said. I remember being gob-smacked by the little boys diving in the water retrieving coins thrown overboard by passengers. After going ashore with Dad he bought something exotic but only had currency worth much more than what he had bought. ” No worry”, the Egyptian trinket seller said in Dutch to dad ( They all spoke all languages). I’ll get the change, just wait.

Dad is still waiting!

Going through the Suez canal was just amazing. Then it was Aden with even more strangeness. Aden -Fremantle took 2 weeks. In Fremantle dad bought lamingtons and a spritzy soft drink from a woman who called my dad “love.”

LikeLike

Thank you all, for your kind comments, though comparisons to Hardy and de Maupassant are probably gilding the hyperbole a little.

This one will require a lot more rigour than The Dogs and will necessitate a lot more research. I’m tossing up whether to go with real people, the innocent and goodhearted people that my family knew there and afterwards, as well as the A Grade sociopaths and the occasional psychopath that made up the staff from time to time; or whether to simply create a believable Fairbridge with no crypto-legal baggage obviating any action for libel.

Anyway there’s still a bit more to finish writing before that decision has to be made. The boys have to get to about 5 or 6 before they’re abandoned to the tender mercies of the Northcott Society and ultimately the Fairbridge scheme.

I should point out that any Old Fairbridgians that stumbles across this are more than welcome to respond with their take on life at Fairbridge. While my recollections of the place remain resonant I realise that being the one of the children of Fairbridge employees makes my sister’s and my experience of the place singularly different to those transported to Molong under the scheme. I find as I get older I need more and more to understand what happened there.

LikeLike

I have to confess that, in my ignorance, had to google Fairbridge. Some references give glowing accounts of the wonderful treatment of the poor orphans, others give much more sinister and cruel accounts.

I grew up within cooee of a couple of well known institutions which purported to bring kids from the bush to the seaside for a holiday and expert medical care. Whilst they probably weren’t anywhere near the level of cruelty as fairbridge, there was a systematic sort of abuse where, for example, kids would come from fairly remote areas for something minor like dental work, tonsillectomy etc, then find themselves still in the institution six months later. These weren’t orphans, but, because of their racial background, their parents ‘wouldn’t really care’!

Like Fairbridge, these places were developed by generous, well meaning people, but degenerated very quickly after the death of the founders.

LikeLike

Therein lay the problem. At Molong it appeared that “out of sight” really did mean “out of mind”. The actions of the Fairbridge Society in London with respect to Molong, made all the worse by chronic financial difficulties with respect to funding the Molong farm, meant that there never really was any chance that the much vaunted and highly connected aspirations of the Lords and Ladies of the Society, anachronistic do-gooding Edwardian throwbacks the lot of them, would never be realised.

Many however, myself included, have nothing but good memories of the place.

Those that genuinely suffered at the hands of grotesques tasked with their care have entirely different stories that quite literally make the hair on your head stand up.

It’s interesting to note that there don’t seem to be similar stories from the Pinjarra WA establishment, which continues to this day, though under far different arrangements than those that prevailed in the past.

LikeLike

I remember watching a TV programme about this last year. They showed footage of the buildings now; footage from archives and interviews with some of the ex boarders. Some were very bitter and recounted their treatment–and some had done well. There was a couple of notable successful people, but I have forgotten their names now.

LikeLike

David Hill, of ABC fame, has co-authored a book. I don’t think he suffered much, as he and his two brothers were only there for two or three years, but he interviewed plenty of his contemporaries, who recount stories of beatings, and so on.

LikeLike

Ah ha, now I remember. Yes it must have been awful. I remember going to boarding school at 12. Mt parents living in another country were un-contactable. It was very confusing and lonely.

LikeLike

One of the things that I think characterised the “Fairbridge experience” for the kids that went there was a kind of emotional and psychological detachment from those around you, other kids and particularly certain members of the staff; and I think this was true whether the individual’s experience was good or bad. Some have had troubled marriages, troubled families, and a life long difficulty with forming secure, trusting relationships. I suspect there was some of this operating in my own parents’ lives.

But Fairbridge and the damage done notwithstanding, David’s version of events; a version that is both convincing and compelling; is still just his version. To balance David’s version I offer Ronnie Sabian’s version ghost written by Jo Bailey. I can’t remember the title off the top, google it. Ronnie’s version is that Woods was a demigod, hard but fair, and frankly that was how he always appeared to me, but then I was only a kid. What did I know? The fact is that a lot of Old Fairbridgians got their noses seriously out of joint over David’s version, as did a lot of folk in Molong. Indeed a public appearance by David to promote his book and discuss his experience had to be canceled because of community grumblings. Or so it came to me.

So the evidence is mounting but the jury still has a lot to sort through. It’s easy to condemn the place as a loveless hell hole where psychopaths tormented children, but that’s a media narrative with about as much truth in it as most media narratives. The actuality for the people who lived it is much more complex, more nuanced.

More like real life.

LikeLike

I can feel the story unfurling with all the pathos and cruelty of the twins arriving at Fairbridge. I hope they survive and get over it. I know and sometimes wonder why I have been so fascinated with the Fairbridge and Molong experiment and can only come up with our treatment at Scheyville Camp. Of course, that pales into insignificance. Even so, the similarity between promises and reality might be the link.

I think it is a tale of cruelty and impending dread, that I am more inclined to think of Guy Du Maupassant rather than T.Hardy.

I hope you will give the twins a gripping tale of survival Waz.

LikeLike

The migrant experience would be common whether Molong or Scheyville.

I should caution you though, lest you think all Fairbridge children and their keepers were either victims or perps. I think it’s fair to say that while there are scarifying stories of casual cruelty and criminal abuse, and nobody had it soft at Fairbridge, none the less many are more than happy to fondly remember their days there.

As I think you and I have discussed in the past G, I have nothing but happy memories, but I also had parents and a genuine “home life”, albeit in an unusual institution.

As for the twins; I hope their lives will reflect the reality of growing up at Molong and the lasting effects that such a childhood would have on them. It is tempting to have one of them die, as a metaphor for loss, but those details are still a long way away. My sense is that they will survive, as Fairbridge Boys do. Further, I suspect that their survival will be because of something essentially Fairbridge, but there’s a lot to get through before any of that needs to be dealt with.

LikeLike

You’re a fine storyteller Waz, I can see this being an enjoyable read like Mongrel and the Runt.

LikeLike

Ta Algy. Let’s both hope it turns out nice again, shall we.

LikeLike

I reckon we could bottle your talent (now) WM.

Excellent. You have set the scene.

Have you ever had Newcastle brown? It’s an acquired taste, but one that gets one’s lips a liken every now and again. I’ve sunk a few.

——————-

The boat trip that took me to Java, for the first time stopped at Cairo; Suez, where we rejoined it after travelling by land–an elected extra–and Aden, as you rightly picked. (More of that one day.)

Then Colombo, when Ceylon was the country’s name. And on to Singapore.

So congrats on your homework!

Your last paragraph: haven’t we all been there–in that dismal well!!?

LikeLike

Too kind, too kind.

LikeLike

You never miss your water ’til the well runs dry.

(was what I’d intended for you VL. The “Too kind” razz was for Big and the Jones boy. I think they’re absolute sweeties.)

LikeLike

Another beautiful story unfolding. So well told , Waz. Many thanks.

LikeLike

I agree, beautifully written ,with such close attention to fine detail, similar to Thomas Hardy (if I may be so bold) who made the lives of common folk so interesting.

Brave midwife delivering preterm twins at home, but, I guess if they were not expected to survive, there was no point adding the costs of hospital care to the family’s woes!

LikeLike